William Chan describes himself as an “activist who pretends to be an artist.” Born in Hong Kong, Chan served more than 10 years in the Army before receiving an MFA in photography, video, and related media from the School of Visual Arts. For the last decade, Chan’s work has explored patriotism and service, resulting in collaborative actions rather than discrete art works. His practice includes mutual aid initiatives, curating, and protest actions. In an artistic climate that often uses politics as window dressing, Chan seeks to avoid performative posturing. His work is anti-metaphorical, directly responding to political crises — including racial inequality, food insecurity, the dearth of resources for migrants, and the ongoing genocide in Palestine. When he and I met in June, weeks before the New York City primary election, he sandwiched our conversation between stints working as a volunteer and Chinatown organizer for Democratic mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani.

Primary final push for mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani; William Chan, center. New York 2025. Photo by Alexandra Chan.

Protest in front of White House. Washington DC 2024.

Chan’s biography lays the foundation for his abiding political commitments. He moved with his family to Manhattan’s Chinatown from Hong Kong in 1983, when he was in the third grade. In 1999, after graduating from college, he joined the Army Reserves — at the time, a low-commitment option for military service. In the early 2000s, Chan worked a corporate day job in the World Trade Center; by lucky happenstance, he was transferred to a midtown office in early 2001, months before the 9/11 attacks. As a reservist, he was deployed to Kuwait on Thanksgiving in 2002 and participated in the first Iraq invasion in March 2003, where he remained on active duty for about four months. After returning to the U.S., he held various roles in the reserves including as a drill sergeant until 2011.

Photo from Ten Years After Iraq, 2015.

Chan has described “romanticizing war and what it meant to be an American” during his overseas tour, but his opinion changed around five years after the war started. His personal reckoning with his military experience resulted in his photo book Ten Years After Iraq, published in 2015. Consisting of 27 pictures taken on disposable cameras during his tour of duty, the tightly edited publication is a haunting chronicle of his day-to-day experiences as a service member. Minimal text accompanies the pictures, distilling repression, regret and mental health struggles into short, piercing lines. The refrain “I’m sorry” reverberates throughout the book, including the final page. On the colophon, Chan includes a message to fellow veterans — “If you’re lost, you’re not alone” — and the contact information for a crisis hotline.

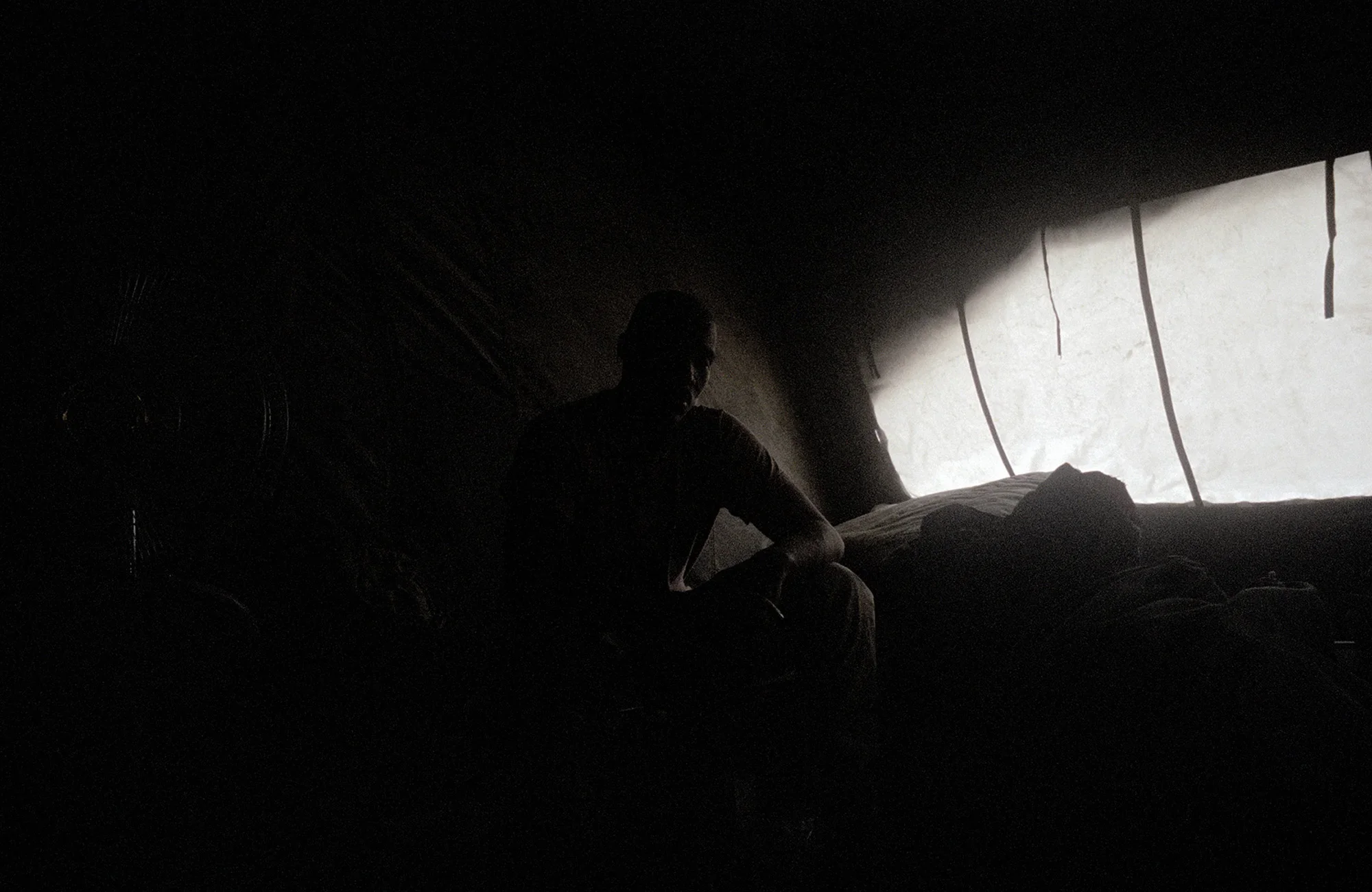

Ten Years After Iraq exposes photography’s failure as much as the medium’s capacity to describe. Moments of joy, tension and sorrow commingle. In one blurry image with a light leak, Iraqi children play and swim in a river. Chan places this image directly after a text-only spread with one sentence about his own son: “Evan will be seven this summer.” Several backlit portraits depict fellow service members in an anonymizing silhouette, relaxing in their tents, their expressions inscrutable. A bleached-out image shows a handwritten sign in English, blowing in the wind on the side of a dirt road. Only partly legible, it reads, “Americans, you did a great [sic] hunorable … don’t make it bad by colonization.”

Photo from Ten Years After Iraq, 2015.

Since the publication of his photo book, Chan’s practice has branched in two directions: in-person direct actions and collaborative organizing. Chan uses the term intervention rather than performance to describe two instances of the former. During the exhibition “Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011” (2019–20) at MoMA PS1 in New York, Chan — whose work was not officially included in the show — spoke uninvited during a curator-led tour about his experiences as a combat veteran. (He also signed the Veteran Art Movement’s letter against the museum’s culture of toxic philanthropy, participating in the actions known as Strike MoMA.) At a rally for then-presidential candidate Andrew Yang in 2020, he praised Yang’s support for de-escalation in Iran.

Chan regularly attends protests and other actions identifying himself as a veteran, sparking conversation and interest from the press. A recent article noted his participation in an April 2025 “emergency Passover seder” at the Immigration and Customs Enforcement headquarters in Lower Manhattan. The event urged the release of pro-Palestinian activist Mahmoud Khalil from detention in Louisiana. Chan carried a sign that read “U.S. Army Veteran, I will not be complicit in genocide, Free Palestine.” The placard echoes part of a statement spoken by Aaron Bushnell, the Air Force service member who live-streamed his self-immolation last year in front of the Embassy of Israel in Washington, D.C.

Jewish Voice for Peace seder. New York 2025. Photo by Emma Guliani.

Forbidden Sign Protest by Hrag Vartanian’s at Home Gallery, 2023.

Chan equally works as an organizer for art and community spaces. He has co-directed artist-run spaces like Transmitter Gallery, Field Projects and Home Gallery, and participated in direct mutual aid actions with artists such as Azikiwe Mohammed and Guadalupe Maravilla. In early 2023, Chan co-organized “Nesting” with curator Eva Mayhabal Davis at the exhibition platform EFA Project Space. The gallery was located a few blocks from Port Authority Bus Terminal, where migrants — particularly from Venezuela — were being sent to New York from Republican states. Chan and Davis described the project as a “sanctuary and mutual aid resource center” for arriving migrants to New York City. The interventions provided by “Nesting” included a “free store” of donated items, as well as art workshops and healing resources like yoga classes and a sound bath.

Chan’s fluid, community-centered practice is rooted in the value of patriotism. In his view, the term patriot has been hijacked by the right wing; he lists true patriots as activists and writers like Angela Davis and James Baldwin, who advocated for liberation across the lines of race, gender and class. In an interview from 2015, Chan spoke directly to his fellow veterans: “If you’re willing to die for your country at one point, if you can give that much, then you need to keep giving ... Keep serving, whatever that might mean.” His actions reveal the myriad ways such service can take shape.

William Chan is a mutual aid organizer, activist, and lecturer. His works on Iraq are taught and held at institutions such as the Tim Hetherington Library at the Bronx Documentary Center, Tate Modern, Yale University, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum, and Harvard University, among others.

Wendy Vogel is a writer and art critic based in Brooklyn, New York. Her work often focuses on issues related to gender, power, identification and body autonomy. She has contributed to many publications about art and culture, including Artforum, Art in America, Art Review, The Art Newspaper, Bookforum, CULTURED, e-flux criticism, Flash Art, frieze, MOUSSE, and The New York Times, as well as artist books and catalogues. In 2018, she received an Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant in Short-Form Writing. She is a part-time assistant professor in the photography department at Parsons School of Design.