Veteran Movements: Seeking Justice & Imagining Reparations installation at Veteran Art Summit and Trinnial, Chicago Cultural Center, 2019. Photo by Eric Perez.

As uprisings for racial justice have emerged across the world this summer, veterans have taken to the streets to stand in solidarity with Black Lives Matter. In May, as officials deployed the military to cities across the country, Veterans For Peace and About Face: Veterans Against the War called on fellow service members to stand down for Black lives. At the end of July, a “Wall of Vets” stood between demonstrators and the violent federal and local police. These actions are the most recent manifestation of veterans mobilizing, organizing, and taking action for peace and justice. There is a long history of veteran activism, which last year’s Veteran Movements exhibition at the Veteran Art Summit and Triennial began to sketch out. In hopes to further lift up the important movement history outlined in the Veteran Movements exhibition, the emerging Veteran Art Movement is republishing an essay about the exhibition.

This is the fourth essay republished by the emerging Veteran Art Movement from the National Veterans Art Museum Triennial & Veteran Art Summit Resource Guide. This summer marks one year since the first-ever Veteran Art Summit & Triennial. Many artists in the emerging Veteran Art Movement network were featured in the Triennial exhibitions (which ran from May through July 2019) and attended the Summit (May 3rd through 5th, 2019). Throughout summer 2020, as a way to acknowledge this historic event and celebrate its success, the emerging Veteran Art Movement will be republishing essays from the National Veterans Art Museum Triennial & Veteran Art Summit Resource Guide.

VETERAN MOVEMENTS: SEEKING JUSTICE & IMAGINING REPARATIONS

May 2019

Veteran Movements: Seeking Justice & Imagining Reparations installation at Veteran Art Summit and Trinnial, Chicago Cultural Center, 2019. Photo by Eric Perez.

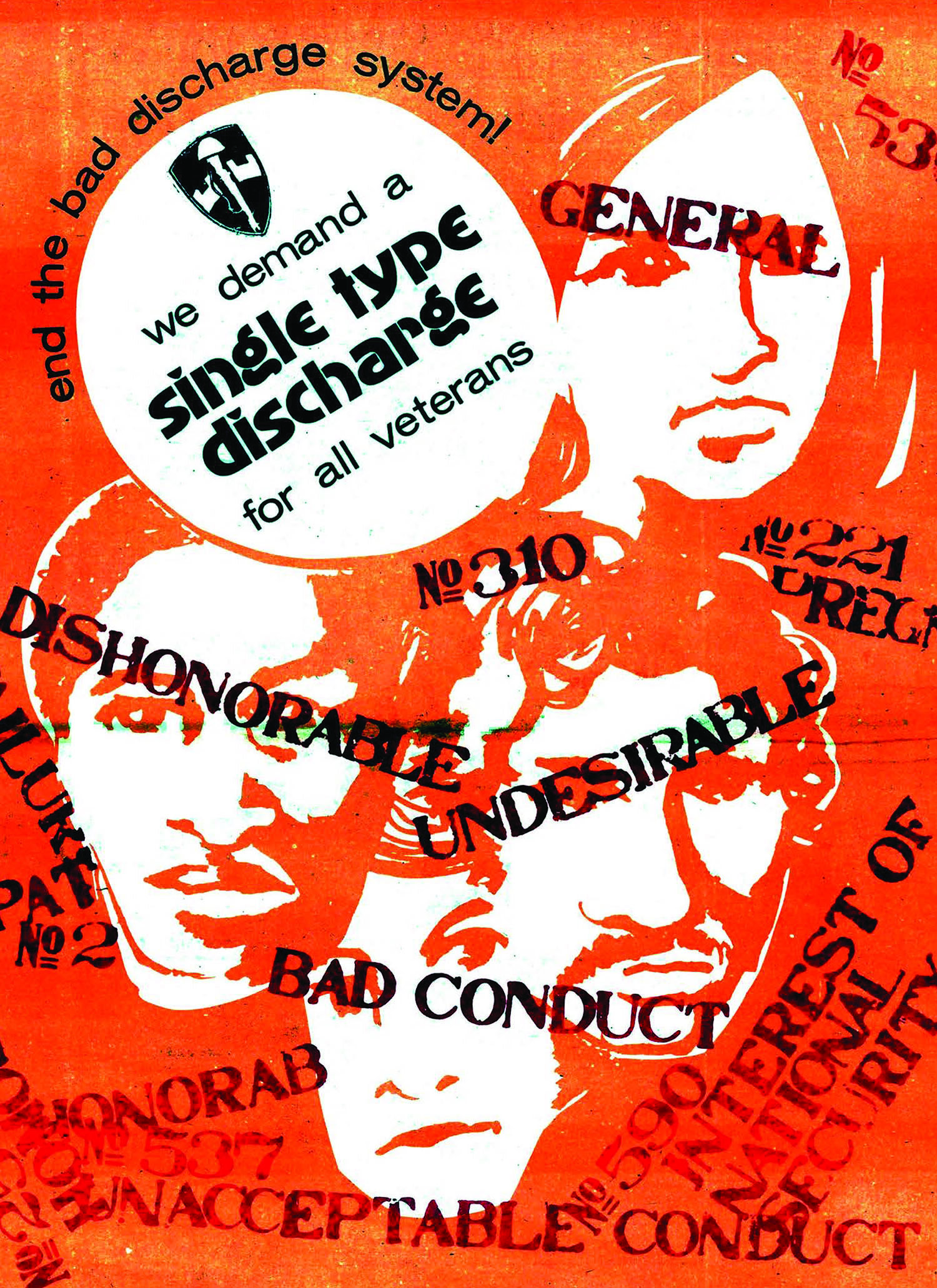

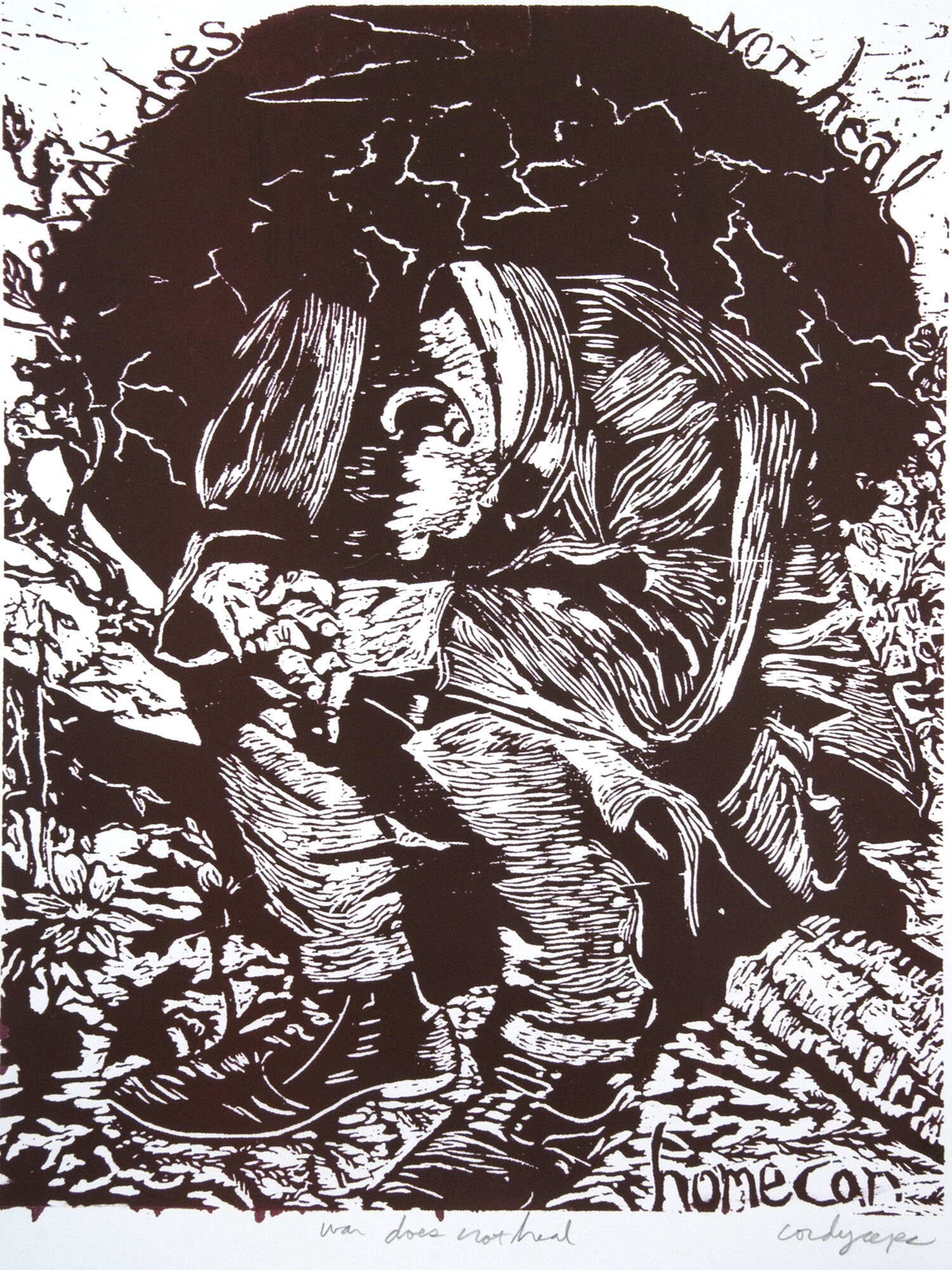

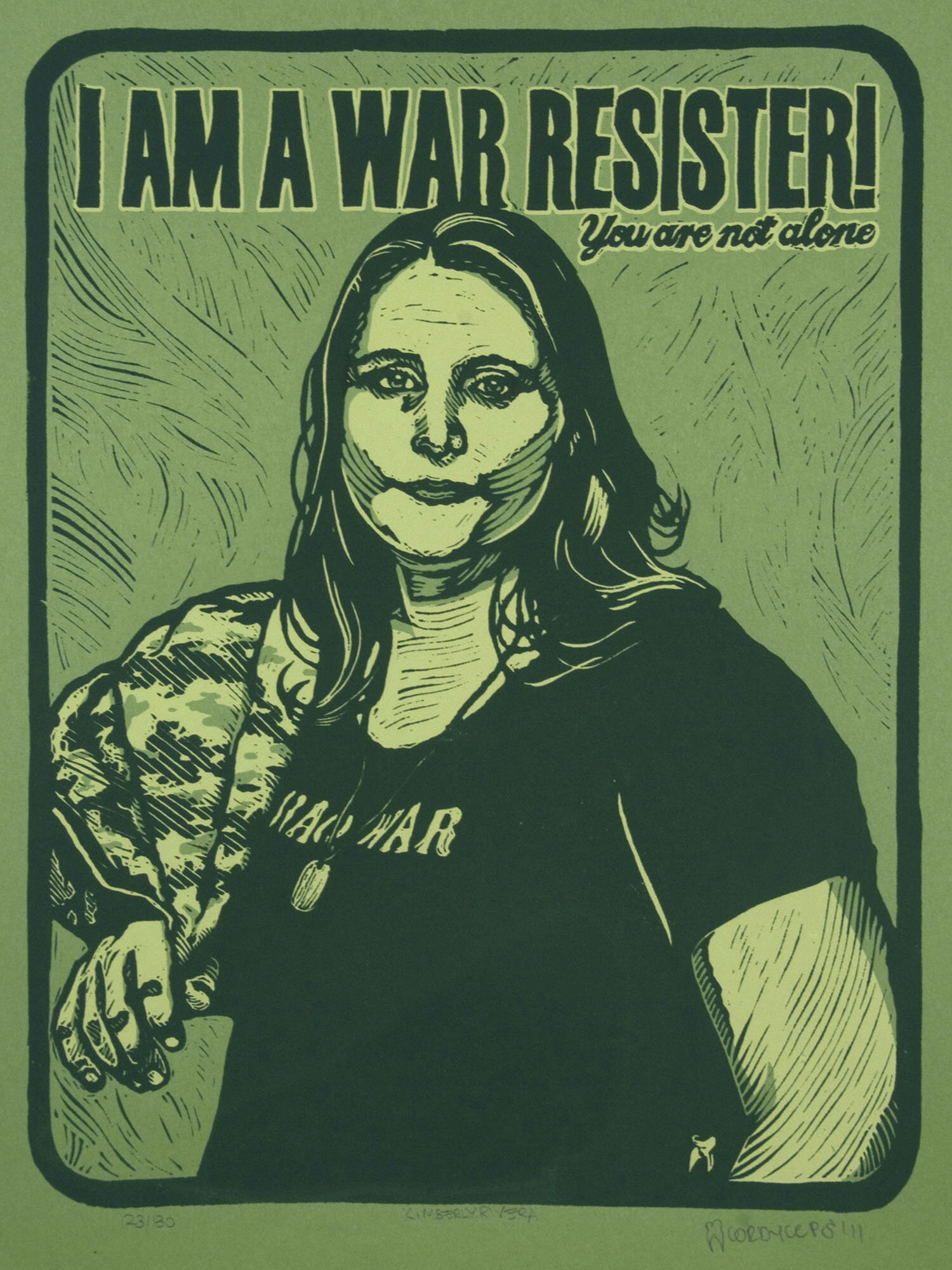

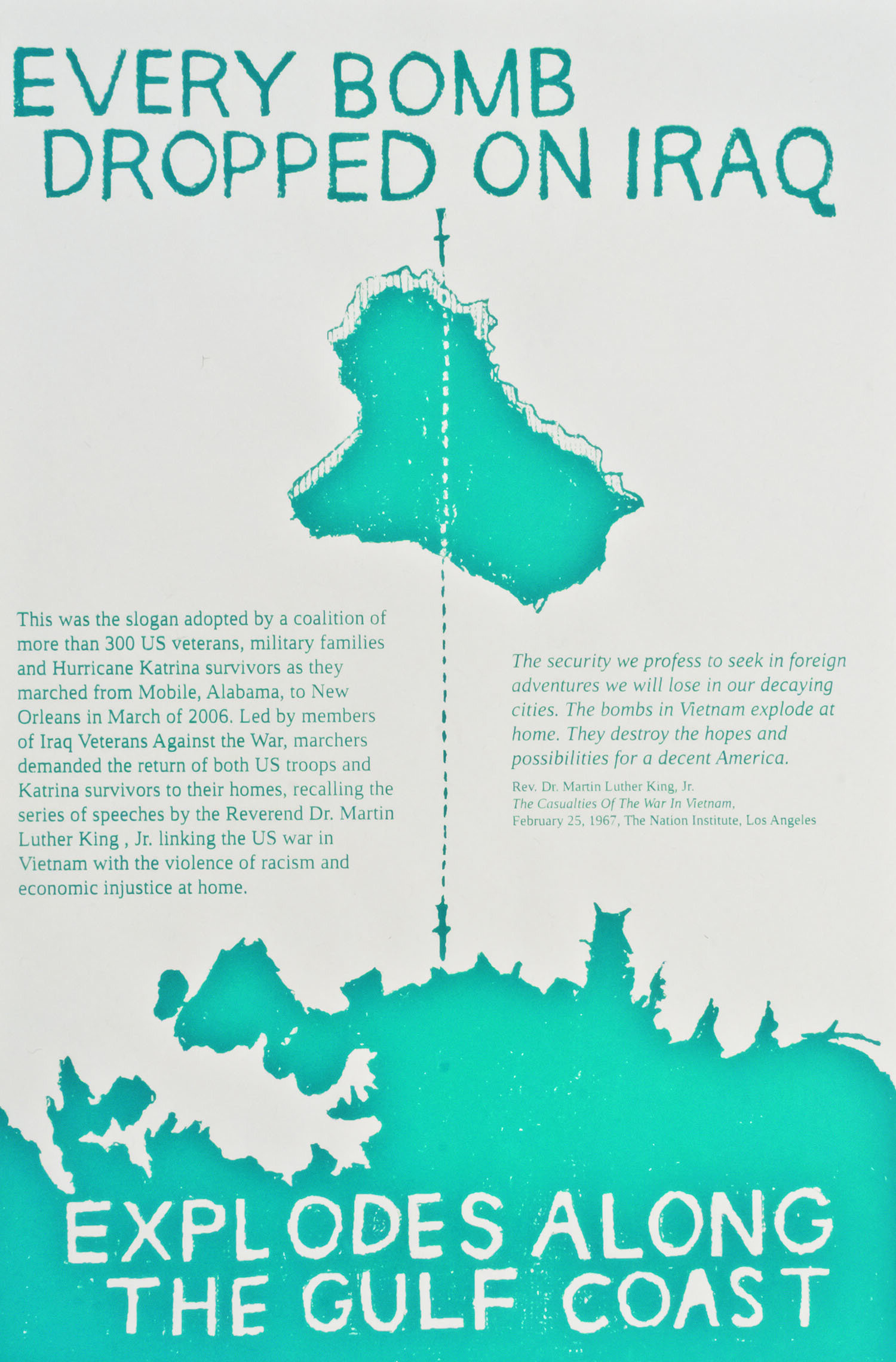

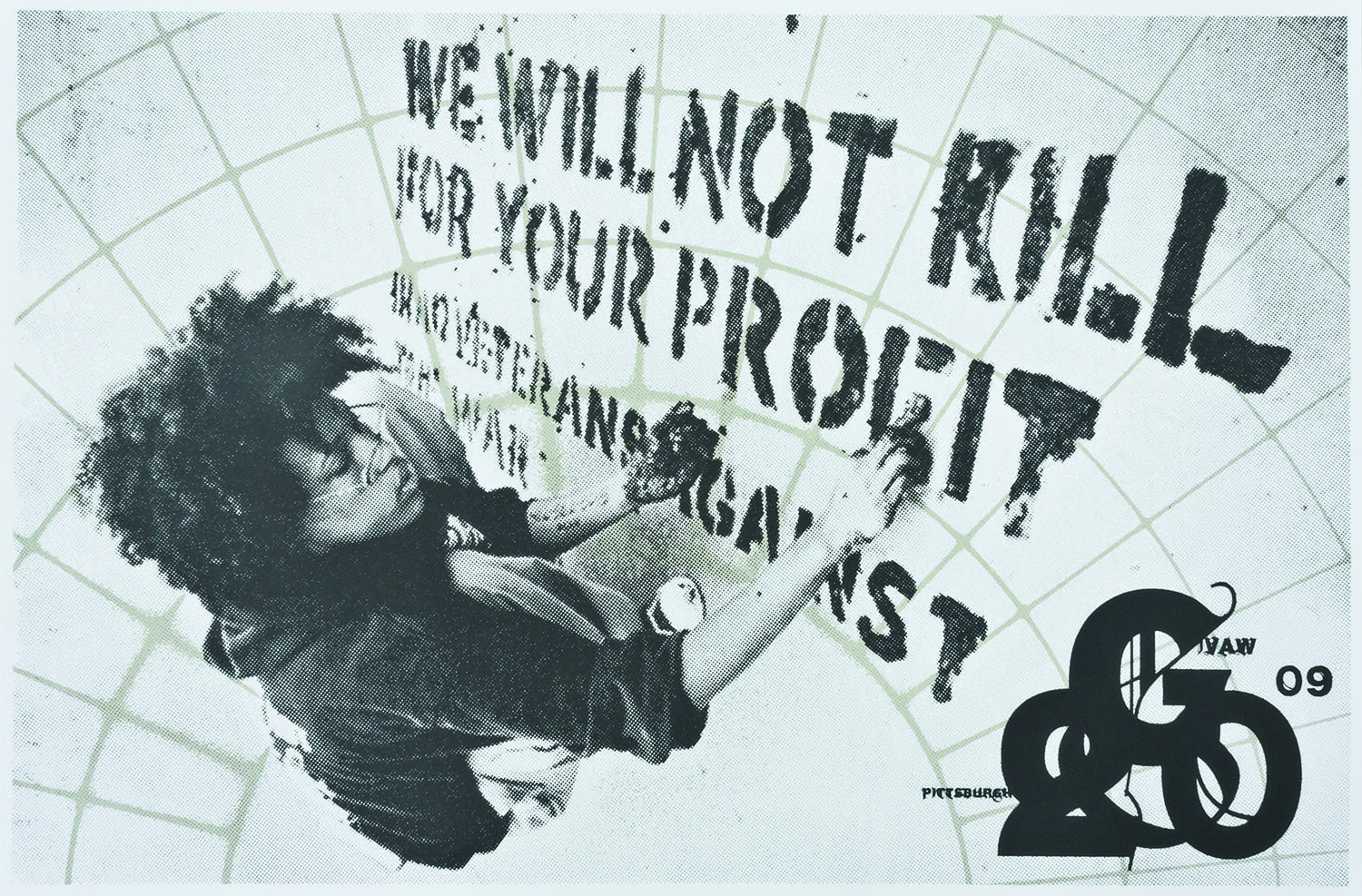

Veteran Movements looks at the inspiring — though often unacknowledged — history of veteran activism. Beyond military service, veterans have long taken action in service of their communities, seeking justice and making peace. To highlight this history, Veteran Movements includes three thematic sections: Dignity, Survival, and Community Reparations. Each section features key moments, figures, and organizations, emphasizing what veterans have fought for beyond their military service. A fourth section, Reclaiming and De-weaponizing, focuses on military tactics veterans have incorporated into their activism. A fifth section features a wall of posters and broadsides produced by (or in collaboration with) veteran movements.

The materials and history displayed in Veteran Movements provide just a glimpse of the long and powerful legacy of veteran activism. This exhibition is meant not only to provide context for the artwork featured across the NVAM Triennial, it’s also meant to spark further research and discussion — by both veterans and civilians — on veterans’ historic and contemporary contributions to social justice and political movements.

DIGNITY

Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world…

— Universal Declaration of Human Rights

For many veterans, what they experienced while serving in the military — both the positive and the negative — has given them a deeper sense of justice and inspired them to take action. There is a long legacy of veterans standing up for the inherent dignity and rights of all people: from Native American World War I veterans fighting for full citizenship, to Black World War II veterans fighting for civil rights in the Jim Crow South, to today’s deported veterans fighting for U.S. citizenship.

Native American Citizenship

Although Native Americans were not legally citizens when the United States entered World War I, more than 12,000 were drafted or volunteered for military service to fight in the war. Many joined in hopes that their service would encourage the government to grant them full U.S. citizenship. Just like African-American troops who hoped that fighting for democracy overseas would help them gain civil rights at home, Native Americans too believed that military service should lead to acceptance within the population they fought for.

Native Americans brought highly useful communication skills to the U.S. military in World War I. The Choctaw telephone squad (an early iteration of “code talkers”) helped keep sensitive information from the Germans by using their language (Choctaw) to pass information. It wasn’t until 1924 when the American Indian Citizenship Right was passed that broad citizenship was granted to Native Americans — though in some states they were still barred from voting until 1957. Notably, in 2019, construction begins on the National Native American Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.

We were forbidden to talk Navajo language up to World War II. And here what they did for the war is the language, the Navajo language. Now it is emphasized that the Navajo language be taught at all schools on the Navajo reservation...the United States government was trying to separate us from our reservation, they had plans to send us out on relocation...but we all came back to the Navajo reservation and tried to stay with the culture.

— Sam Smith, Code Talker, Marine Corps, from the Library of Congress

Wounded Knee 1800-1973, The Winter Soldier Newspaper, Vietnam Veterans Against the War, May 1973.

Civil Rights

After fighting for liberty abroad, many African American World War II veterans returned home to face racial injustice in America. This was especially true for those living in the South under Jim Crow laws, which prevented African Americans from voting. This oppressive treatment prompted many African American veterans to organize some of the first voter registration drives and help build an emerging Civil Rights Movement. The many African American veterans who joined the fight include Medgar Evers, who became a leader within the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and Amzie Moore, who worked with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

Army Lieutenant Colonel John Boyd, a well-regarded military strategist, once said, “...if it wasn’t for the black Soldiers who came back from World War II and the Korean War and lent their expertise to the cause, Dr. King and the other ministers would not have been able to effectively organize as they did.”

[Medgar Evers speaking at NAACP civil rights event ca. 1960s.] Evers, Medgar Wiley, Myrlie Evers-Williams, and Manning Marable, The Autobiography of Medgar Evers. Skyhorse Publishing, 2005.

[Vietnam Veterans Against the War at Medgar Evers Grave] VVAW Archives, ca. 1971.

LGBTQ Rights

“Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” refers to the official United States policy on military service by gays, bisexuals and lesbians, instituted by the Clinton Administration on February 28, 1994. The policy prohibited military personnel from discriminating against or harassing closeted homosexual or bisexual service members or applicants, while barring openly gay, lesbian, or bisexual persons from military service. Prior to “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” gays and lesbians were prohibited from serving in the military. Thanks to the efforts of the veteran community, the landmark federal statute “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Repeal Act of 2010” was enacted in December of that year. This act allows gays, lesbians, and bisexuals to serve openly in the United States military. Activism by LGBTQ veterans during the course of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” helped set the stage for future movements by the LGBTQ population.

[Leonard Matlovich reads the Time Magazine Article about himself] LeonardMatlovich.com, ca. 1975.

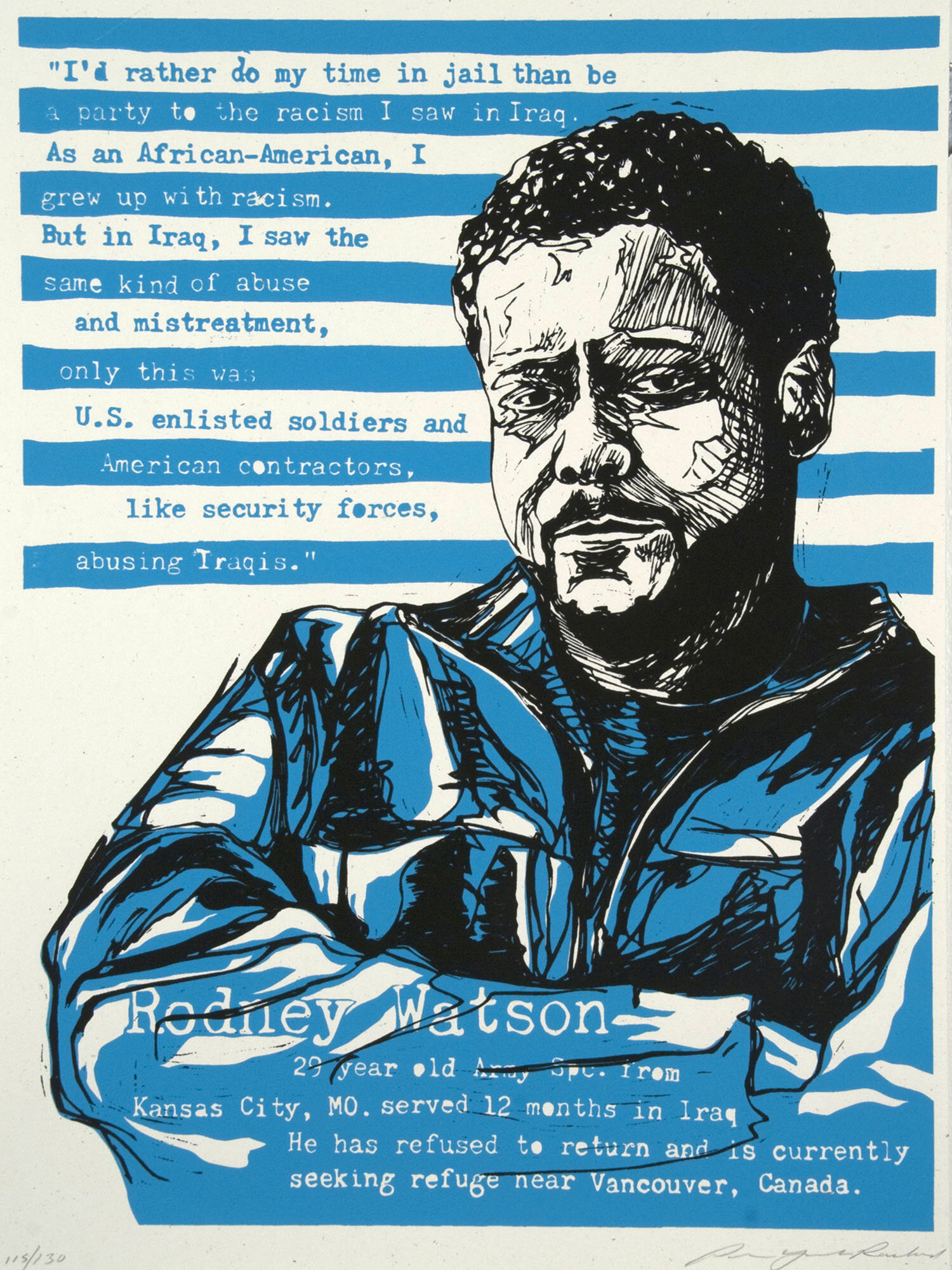

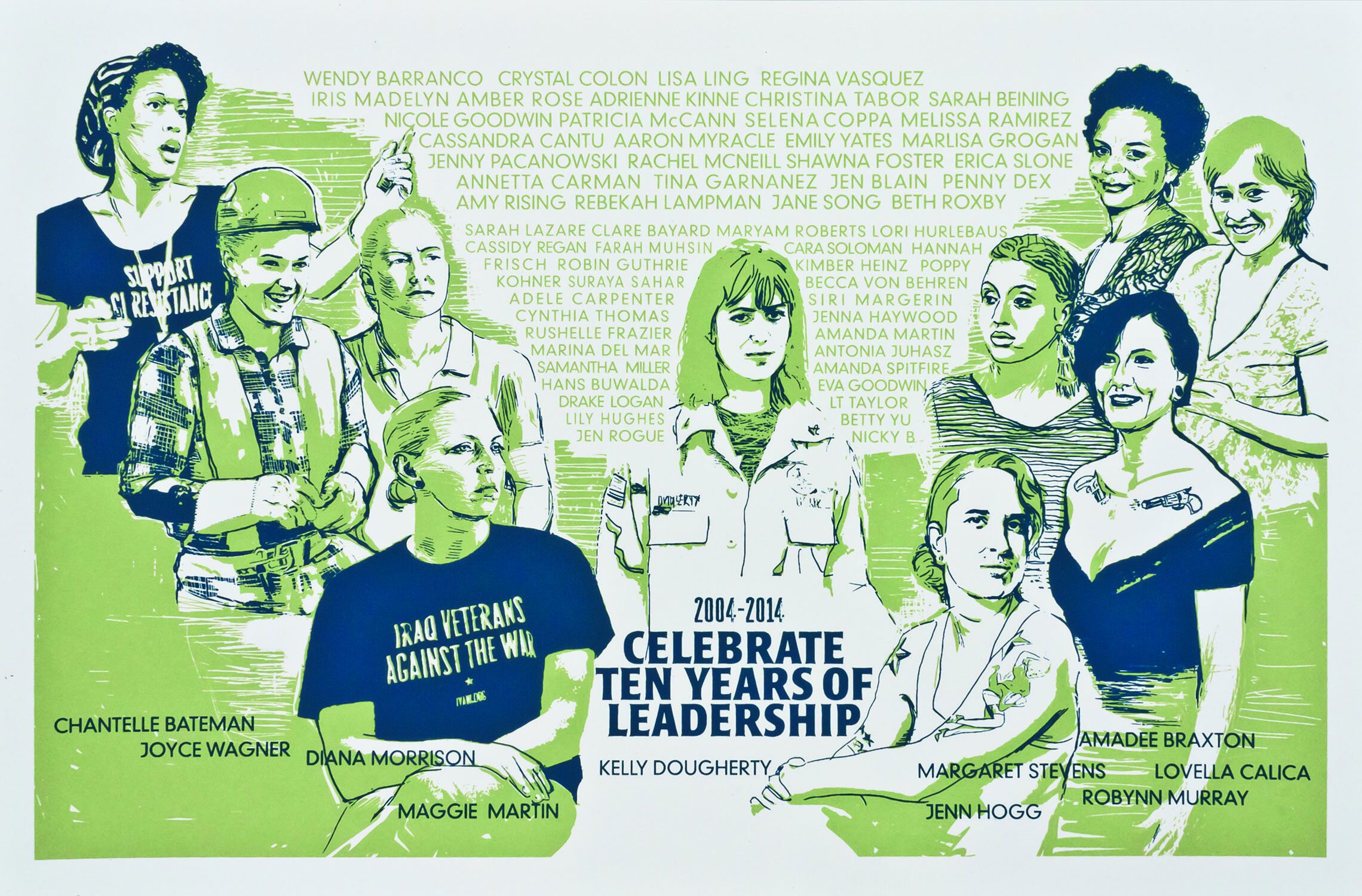

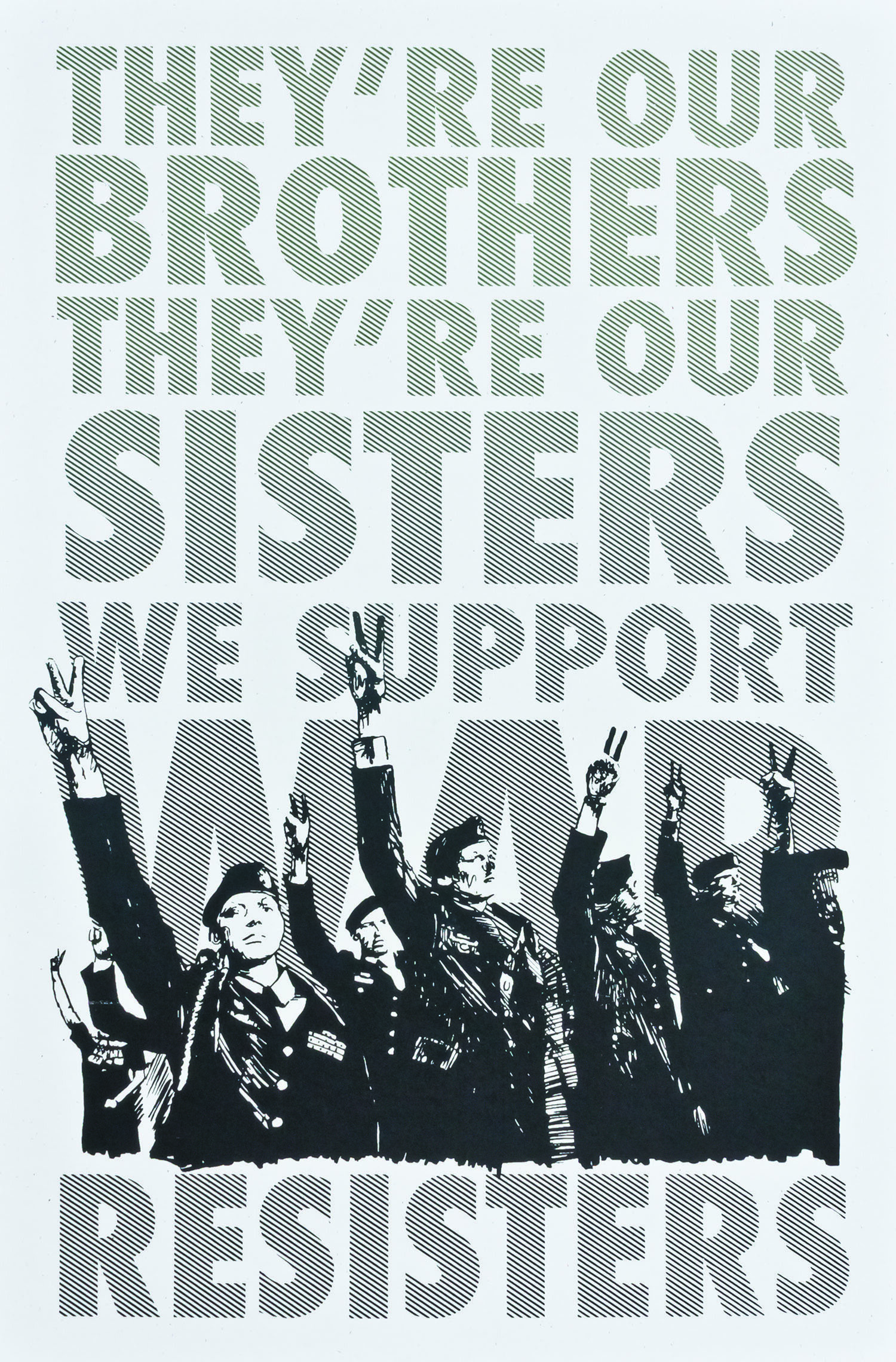

Jesse Purcell, Jeff Key, Celebrate People’s History: IVAW poster portfolio, 2014.

Gender Equality

The Service Women’s Action Network (SWAN) was founded in 2007 as a member-driven community that advocates for the individual and collective needs of servicewomen. To date, SWAN has played a major role in shaping the outcome of many important issues affecting women in the service, including opening all military jobs to women and holding sex offenders accountable to the military justice system. The network continues to work on eliminating barriers to disability claims for those who have experienced military trauma and expanding access to a broad range of reproductive health care services.

#MeTooMilitary, Service Women’s Action Network, 2011-2012.

Trans Inclusion

On July 26, 2017, President Donald Trump announced that transgender people would no longer be allowed to serve in the U.S. military. On August 1, 2017, the Palm Center research institute released a letter signed by 56 retired generals and admirals opposing the proposed ban on transgender military service members. The letter stated that, if implemented, the ban “would cause significant disruptions, deprive the military of mission-critical talent and compromise the integrity of transgender troops who would be forced to live a lie, as well as non-transgender peers who would be forced to choose between reporting their comrades or disobeying policy.” On March 23, 2018, President Trump officially banned transgender and transsexual people with current or previous gender dysphoria from serving in the U.S. military.

[“It’s all about the climate your command creates. My command was really helpful. He told everyone, ‘She will be respected. Discrimination will not be tolerated.”] Jeff Sheng, Smithsonian, “The Faces Behind Transgender Troops’ Struggle for Acceptance”; vol. 49, no. 9, 2019.

Military Service to Citizenship

The organization Green Card Veterans works closely with the larger veteran community to address and advocate for the rights of non-citizen U.S. service members, veterans and their families, and Gold Star families. Formed in 2017, Green Card Veterans fights for those who are at-risk or under an order of deportation, striving to give their disenfranchised veteran brothers and sisters, as well as their families, a fighting chance and a voice. Their ultimate goal is to end the exile of veterans and repatriate veterans who have been deported, through community organizing, advocacy, and research.

[Protest at the San Ysidro-Tijuana Border Port of Entry, San Diego] April Arreola, 2010.

SURVIVAL

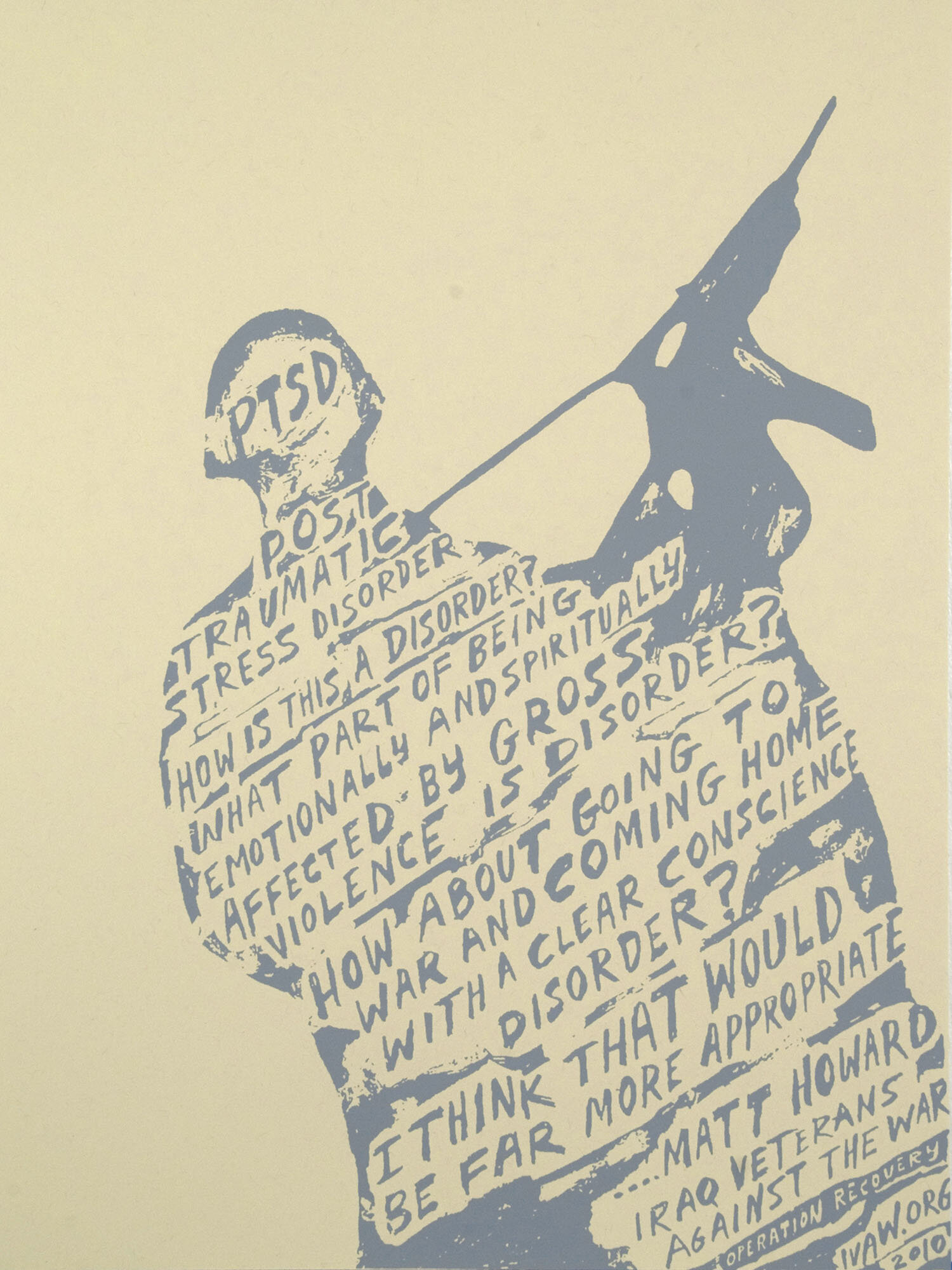

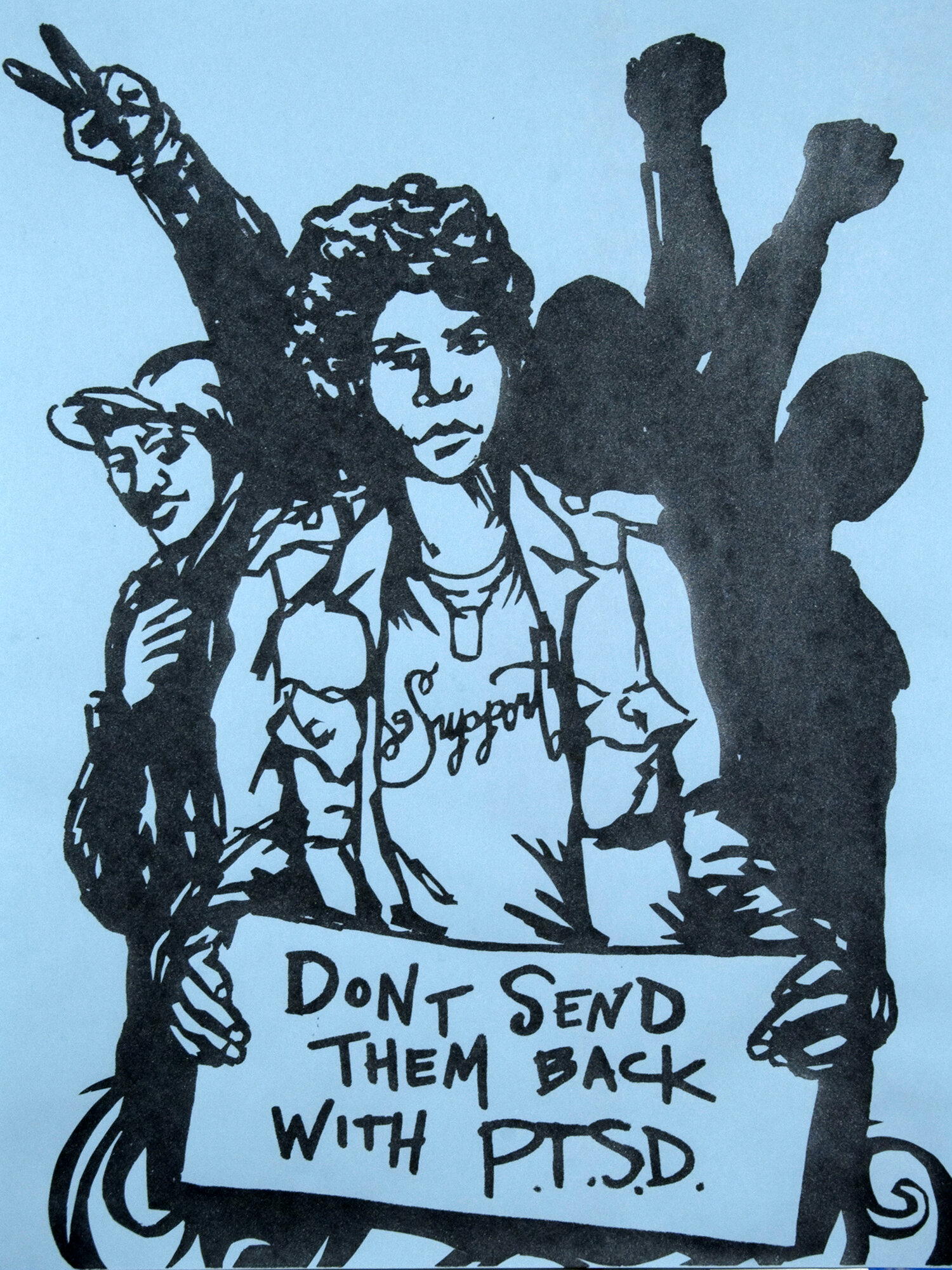

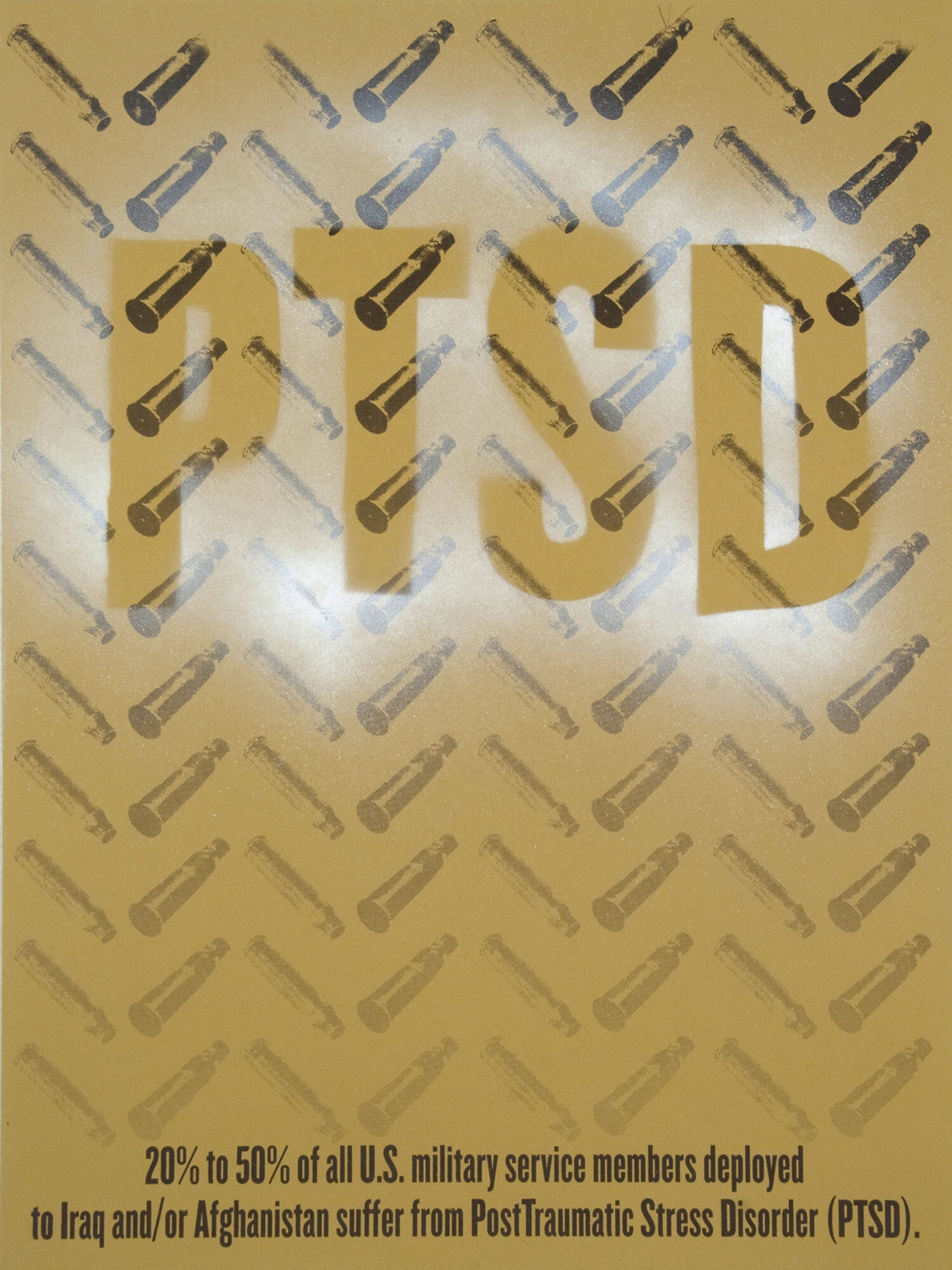

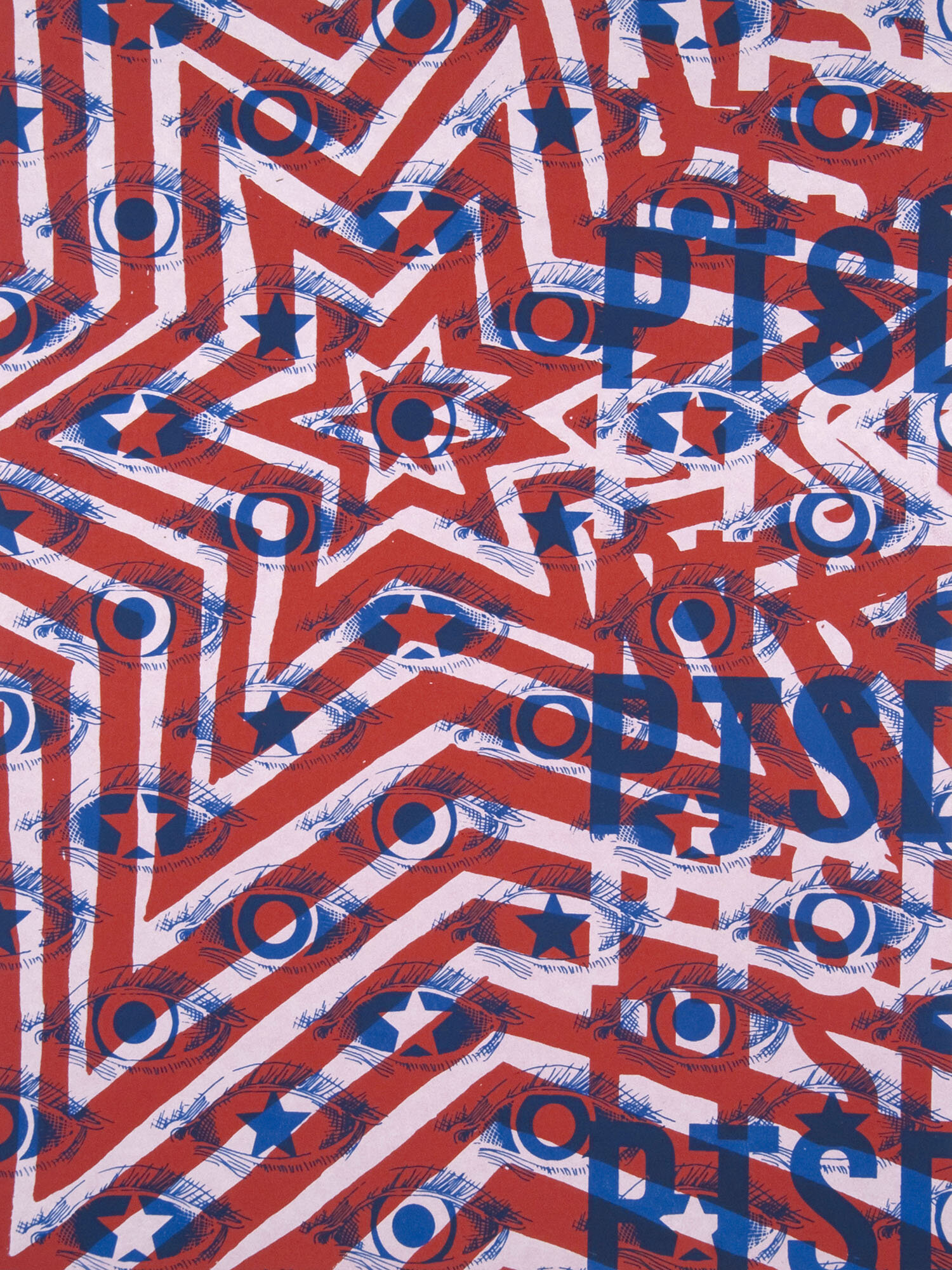

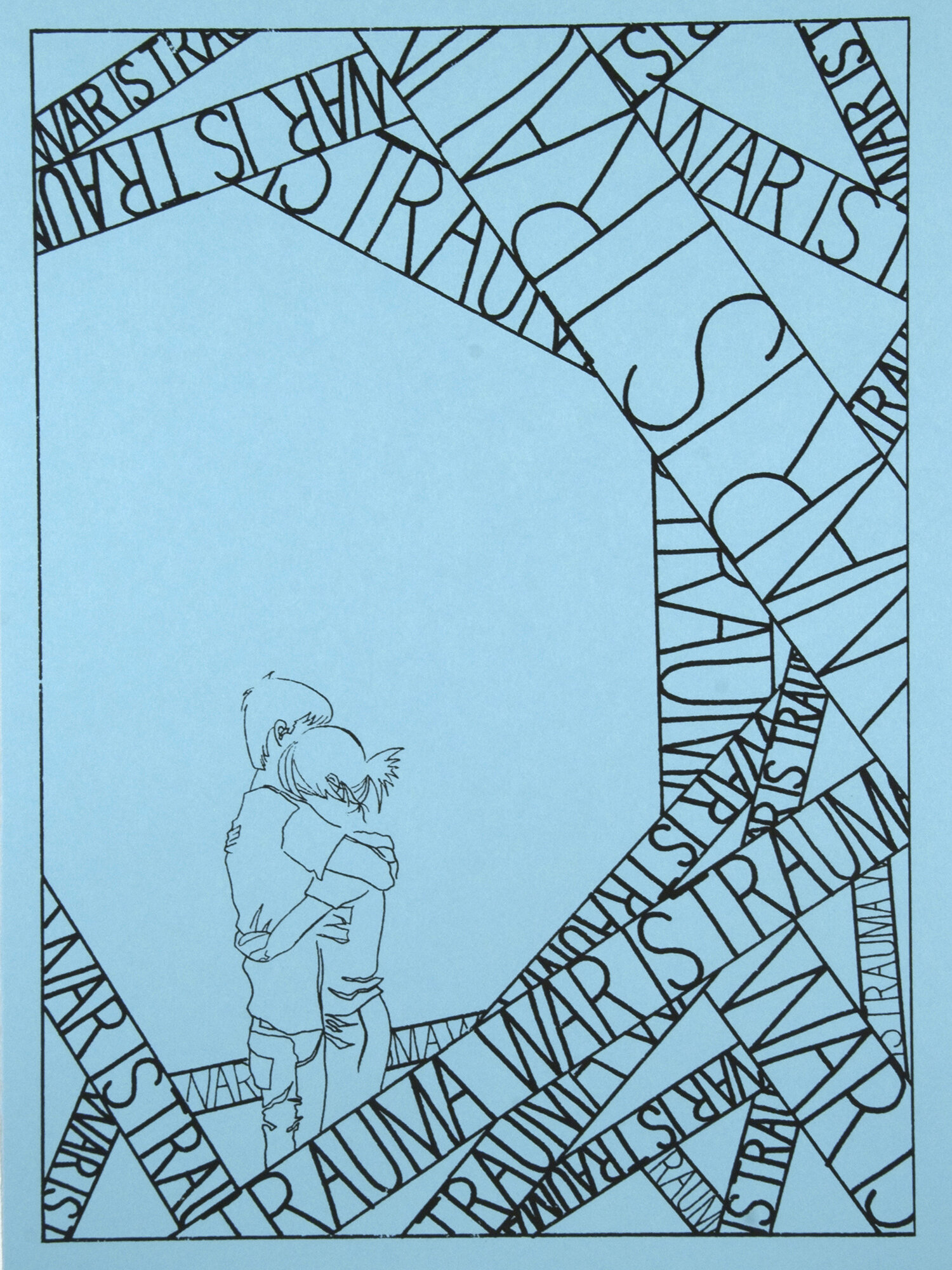

Service members and veterans do not only fight for survival on the battlefield, but also on military bases and at home. Military sexual trauma, moral injury, post traumatic stress disorder, drug addiction, homelessness and suicide are just some of the challenges many face. However, veterans and service members have long taken action to address these issues, often through self-organizing. For the many who have spoken out and worked towards ending these problems, survival — both for oneself and the community — becomes an empowering political act.

AIDS Crisis

Veterans have directly impacted and helped shape disability rights legislation. Over the last 100 years, disabled veterans have fought for better treatments for PTSD, MST (Military Sexual Trauma), AIDS and more. As of 2010, the Veterans Health Administration (VA) has been the largest single provider of HIV treatment in the United States, providing care for more than 24,000 veterans living with HIV. Clarence Fitch, a Marine who served in the Vietnam War, became an icon for veterans living with AIDS through his activism with Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW).

People started trying to educate themselves about how the war started, where the war was going...for the first time we were really looking at the enemy not so much as the enemy, but as another minority...the war in Vietnam was not stopped by politicians, the war in Vietnam was stopped by people getting out into the streets and saying this is wrong.

— Clarence Fitch, Another Brother documentary

[Clarence Fitch was an inspiration to hundreds of young people who witnessed his strength, resilience, and clarity of vision.] William Short, VVAW, The Veteran, vol. 28 no. 1., ca. 1980s.

Right to Heal

The Right To Heal Campaign was started by veterans on the tenth anniversary of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, with intentions of holding the U.S. government responsible for the damaging effects of the Iraq War on service members and civilians. The campaign recognizes that the war is not over for those who served, as well as for Iraqi civilians who continue to grapple with various forms of injury, trauma and displacement. In a joint initiative with Iraqi human rights organizations, the veterans have demanded that the real impacts of the war be assessed and concrete action be taken towards providing reparations and rehabilitation.

[Operation Recovery March Washington D.C., Veterans Day] IVAW Archives, 2010.

[Operation Recovery Guard Tower at Fort Hood] IVAW Archive, 2011.

Sexual Assault

The #MeToo movement is not only a phenomenon within the civilian population, but also within the military and veteran community. Veterans who have survived sexual assault while serving — Military Sexual Trauma (MST) — are more likely to experience stress, depression and other mental health issues, leading to higher rates of substance abuse and difficulty finding work after discharge. Breaking the stigma of talking about MST encourages survivors to seek assistance, while also helping to mitigate challenges others may face when they too decide to come forward. For example, in March of 2019, Senator Martha McSally, the first woman to fly in combat, testified before the U.S. Senate about being raped by a superior officer while serving, as well as other MST she endured. This has inspired others to share their experiences. MST-related activism (such as pushing for better training programs), as well as sharing personal experiences, marks a first step towards equity and justice.

Siri Margerin, Maggie Martin, 2010.

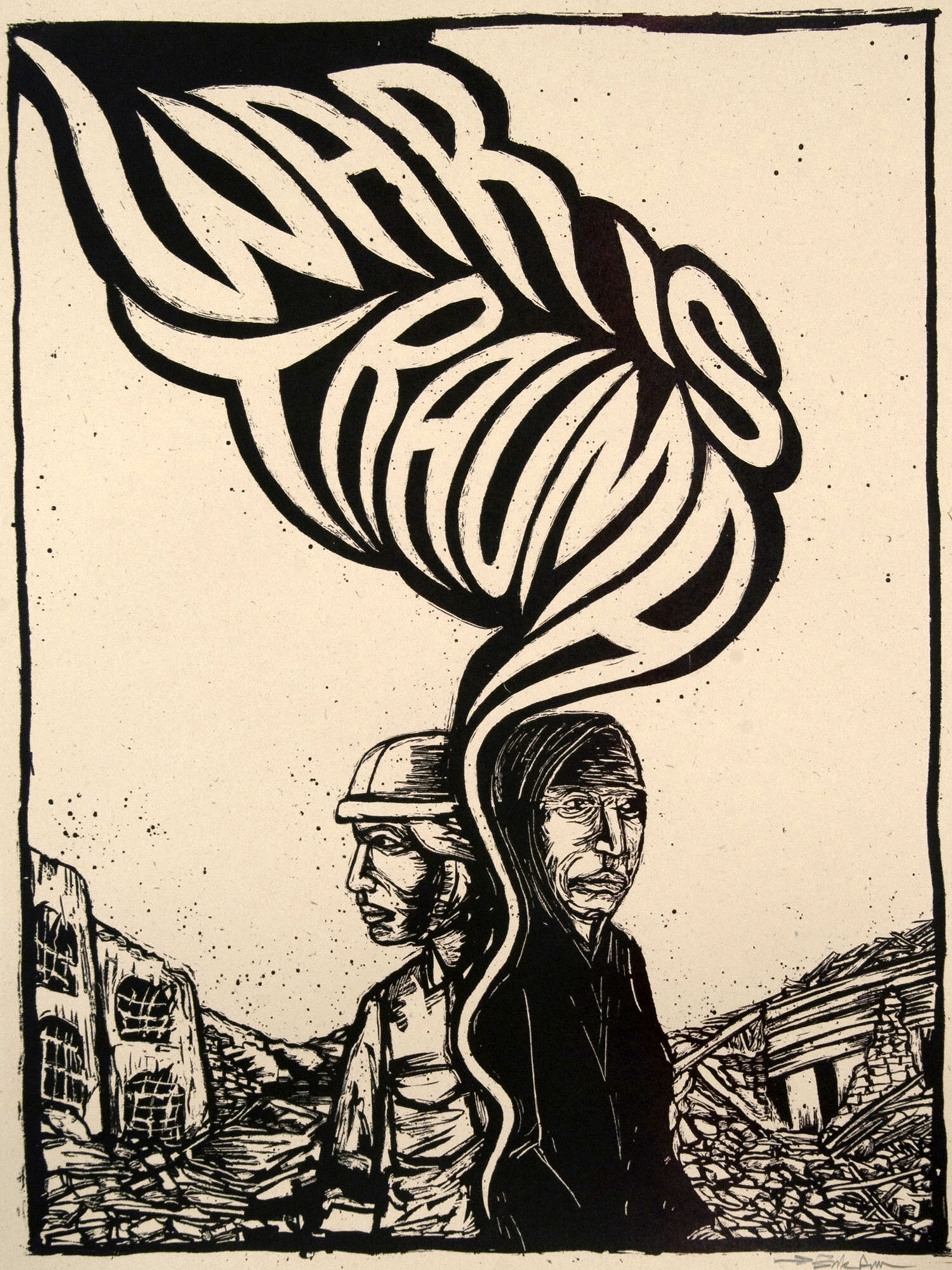

IMAGINING REPARATIONS

Veterans have taken responsibility for the wars they helped perpetrate. They have taken action to compensate people for the violence that has decimated families and communities, destroyed fertile lands and ruined infrastructures. Vietnam Veterans Against the War advocated for victims of diseases caused by Agent Orange use in Vietnam. Afghanistan veterans have gone back to the country where they once fought, to support schools there. Iraq Veterans Against the War have called for reparations for the Iraqi people. These demands and efforts are often made in hopes of inspiring all U.S. citizens to take responsibility for the destruction and instability caused by wars waged in their name.

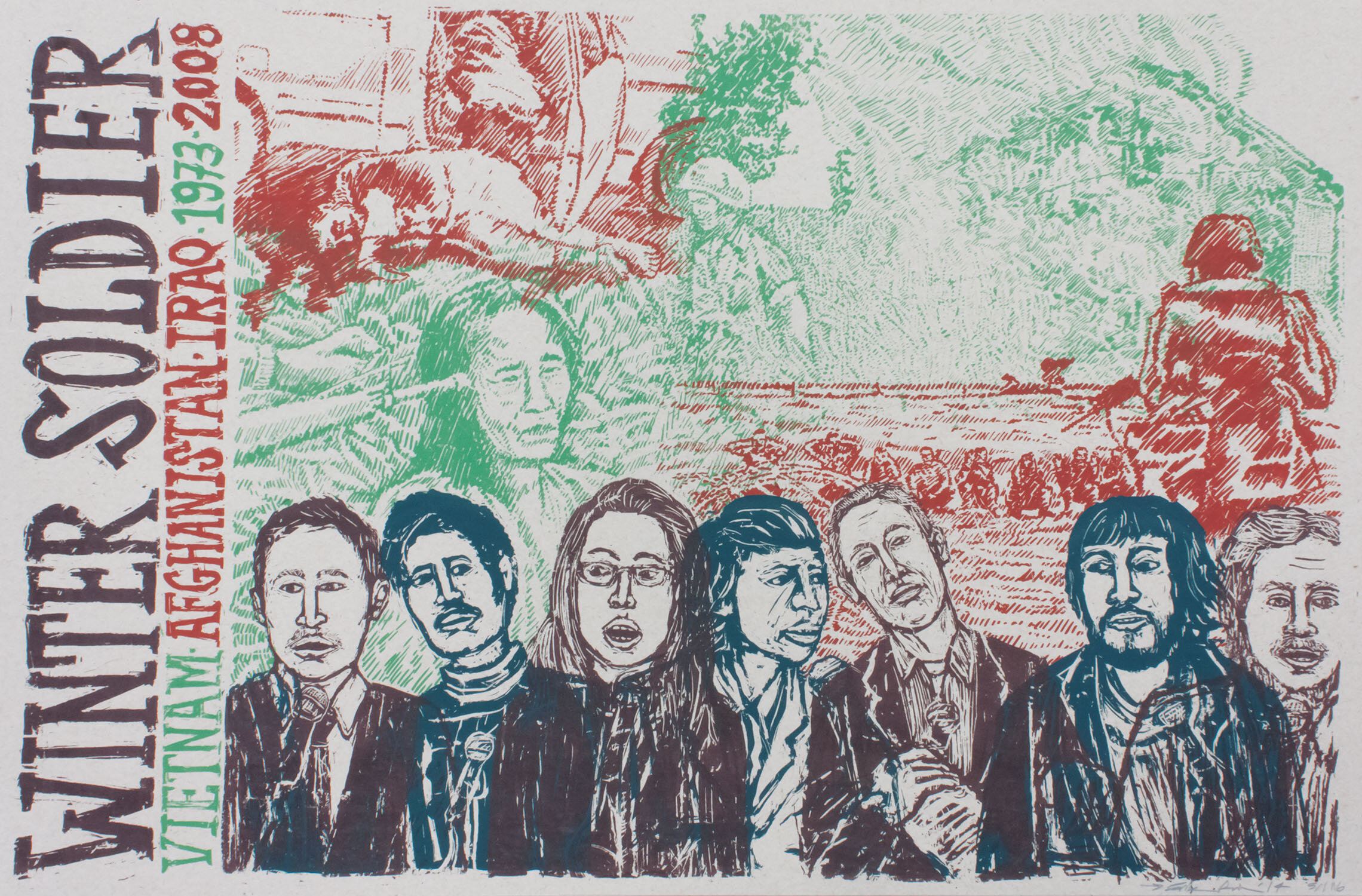

War itself is a crime. Yet a war crime is more and other than war. It is an atrocity beyond the usual barbaric bounds of war. [...] Deliberate destruction without military purpose of civilian communities is a war crime. The use of certain arms and armaments and of gas is a war crime. The forcible relocation of population for any purpose is a war crime. All of these crimes have been committed by the U.S. Government over the past ten years in Indochina. An estimated one million South Vietnamese civilians have been killed because of these war crimes. A good portion of the reported 700,000 National Liberation Front and North Vietnamese soldiers killed have died as a result of these war crimes and no one knows how many North Vietnamese civilians, Cambodian civilians, and Laotian civilians have died as a result of these war crimes.

— William Crandell, 199th Brigade, Americal Division; 1971 Winter Soldier Investigations

Iraq & Afghanistan Reparations

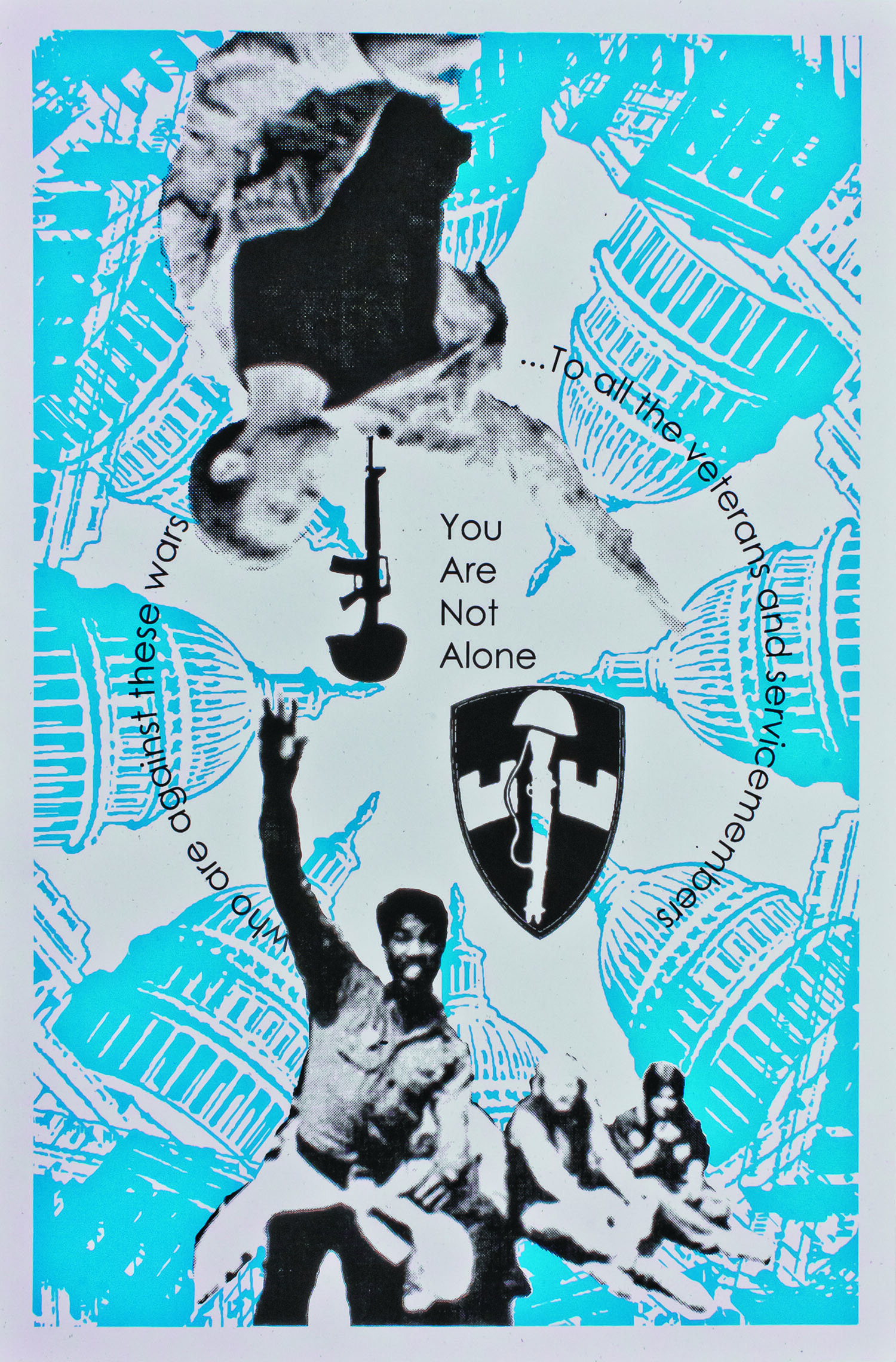

Since the founding of Iraq Veterans Against the War in 2004, the organization has fought for “reparations for the human and structural damages Iraq has suffered.” IVAW’s mission later expanded to include other countries the U.S. military has occupied. To this day, IVAW (now called “About Face: Veterans Against the War”) continues to emphasize the importance that all Americans take responsibility for the wars waged in their name, in a push towards restorative justice. By partnering with organizations like Afghan Peace Volunteers, Afghans for Peace, and The Islah Reparations Project, veterans in the U.S. have helped support projects and programs created by these groups, in an effort to help foster peace and nonviolence.

[Afghanistan Veterans and Afghans for Peace speak at Nato Protest] Siri Margerin, 2012.

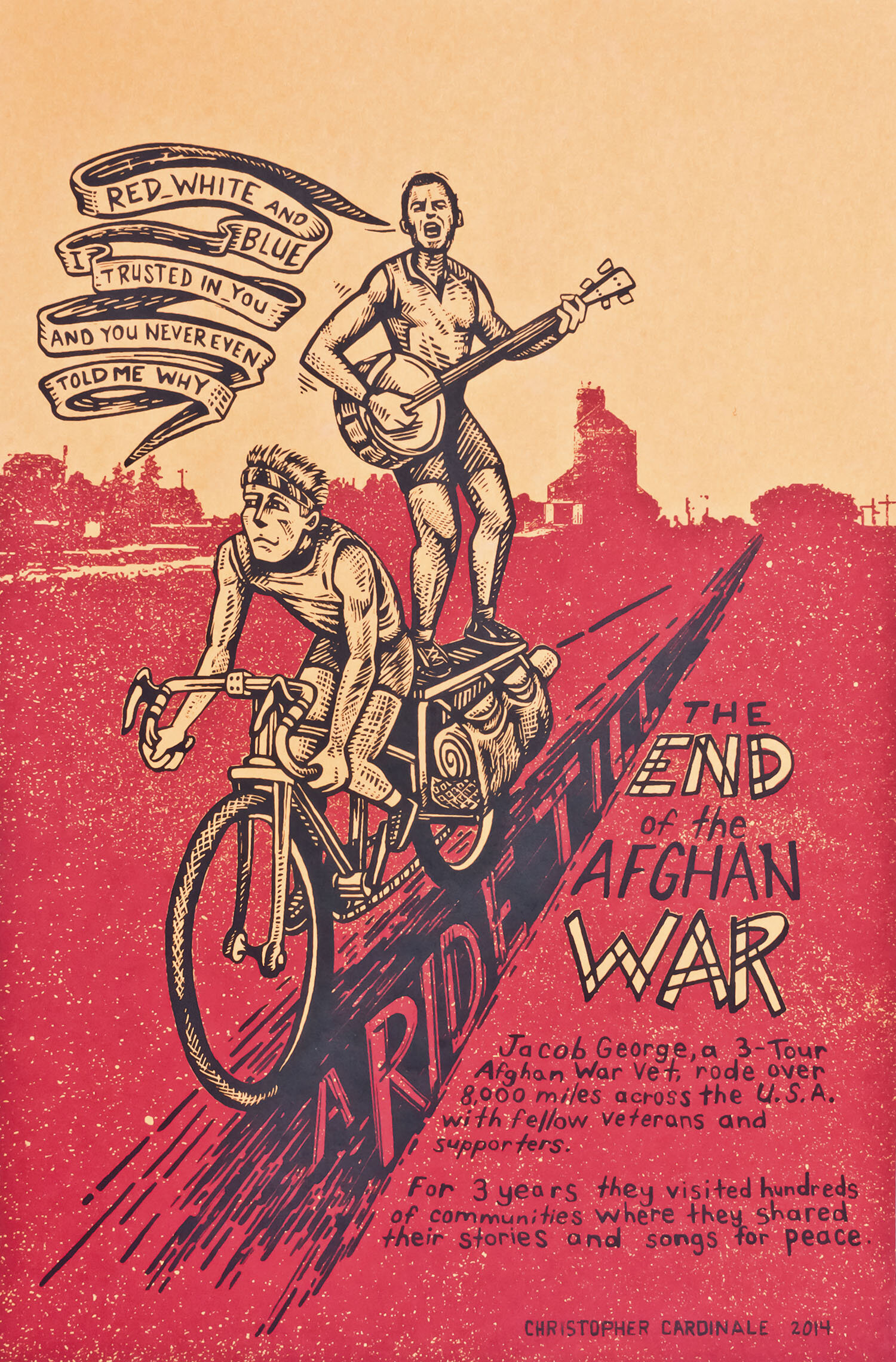

[Jacob George Returns Medals to NATO Summit] Siri Margerin, 2012.

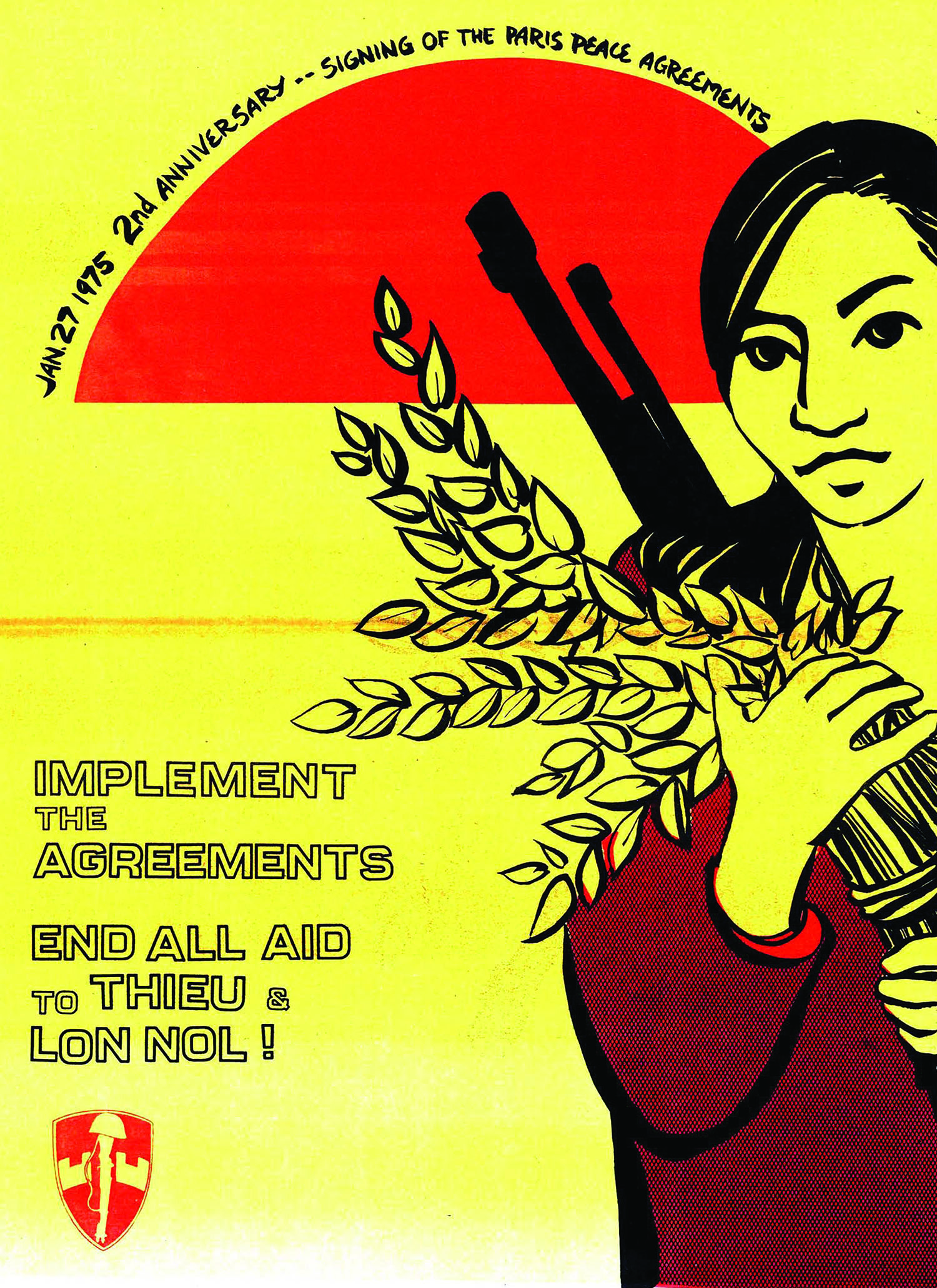

Agent Orange Reparations

Although the U.S. now provides benefits to U.S. veterans who were exposed to the harmful defoliant chemical Agent Orange, the same aid is not offered to the Vietnamese who were also exposed. Vietnam Veterans Against the War began advocating for both American and Vietnamese victims in 1971 and continues this fight to the present day. Although the U.S. military no longer uses Agent Orange, the effects of its use in Vietnam 50 years ago still significantly affects the Vietnamese people and the environment.

[Crop duster airplanes spray Vietnamese countryside] Creative Commons, 1966.

[Aerial herbicide spray missions in southern Viet Nam, 1965 to 1971] The Veteran, vol. 38 no. 2, VVAW Archive.

Annie Bailey at Agent Orange settlement hearings in 1984. VVAW Archive, 1984.

RECLAIMING & DE-WEAPONIZING

There is a long history of veterans using skills and tactics they learned in the military to support social justice and political movements. For example, in 1932 a desegregated group of thousands of veterans set up a military-style encampment in Washington D.C., to nonviolently demand fair compensation for having fought in World War I. This marked the first occupation of the National Mall area of the nation’s capital. In the following decades, this tactic would be used by other movements, from the Poor People’s Campaign to Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Most recently, veterans from around the country traveled to South Dakota to join the Standing Rock Sioux at their encampment blocking the Dakota Access Pipeline, to help protect indigenous lands.

Bonus Army Movement

In the summer of 1932, the “Bonus Expeditionary Force,” made up of some 40,000 marchers (mostly U.S. World War I veterans, their families and supporters) gathered in Washington, D.C. to demand fair compensation for the veterans’ World War I service. The group’s name was a play on “American Expeditionary Force,” the World War I allied coalition organized by the United States. The so-called “bonus” referred to service certificates — money — that had been promised to them in 1924 by Congress (after much advocacy and activism), to help match the pay their civilian counterparts had earned during the war. The Great Depression had plunged many veterans into poverty and unemployment, and keeping the money locked up in the certificates frustrated them even more (the certificates couldn’t be redeemed until 1945 — no doubt many veterans would have been deceased by then). After a series of failed legislation proposing immediate payment, the 1932 “Patman Bonus Bill” is ultimately what motivated the massive Bonus Army mobilization. Upon arriving in the capital, the veterans built a military-style encampment and temporary housing units along the Anacostia River, as well as occupied sections of the city itself. In the coming weeks, after the Patman Bonus Bill got voted down, these camps would get shut down by President Hoover’s order, and the veterans and supporters routed out of the city by the U.S. Army. But veterans kept returning to Washington, pushing for redemption of the certificates. Finally, in 1936, the Bonus Bill was passed and veterans received compensation. This legislation would lay the groundwork for the 1946 G.I. Bill, which provided education, housing and other benefits for service members returning from World War II (and future generations of veterans too).

[Bonus Army aboard train cars heading to Washington D.C.] Underwood & Underwood, Library of Congress Prints & Photo Archive, ca. 1931-1932.

[Crowd on steps of the U.S. Capitol on the arrival of a bonus petition signed by over 1,000,000 veterans.] Library of Congress Prints & Photo Archive, ca.1922.

[Veterans march to Washington to arrive at opening of Congress, December 5th, 1932 to demand cash payment of bonus.] Veteran’s Rank & File Committee, Library of Congress Prints & Photo Archive, 1932.

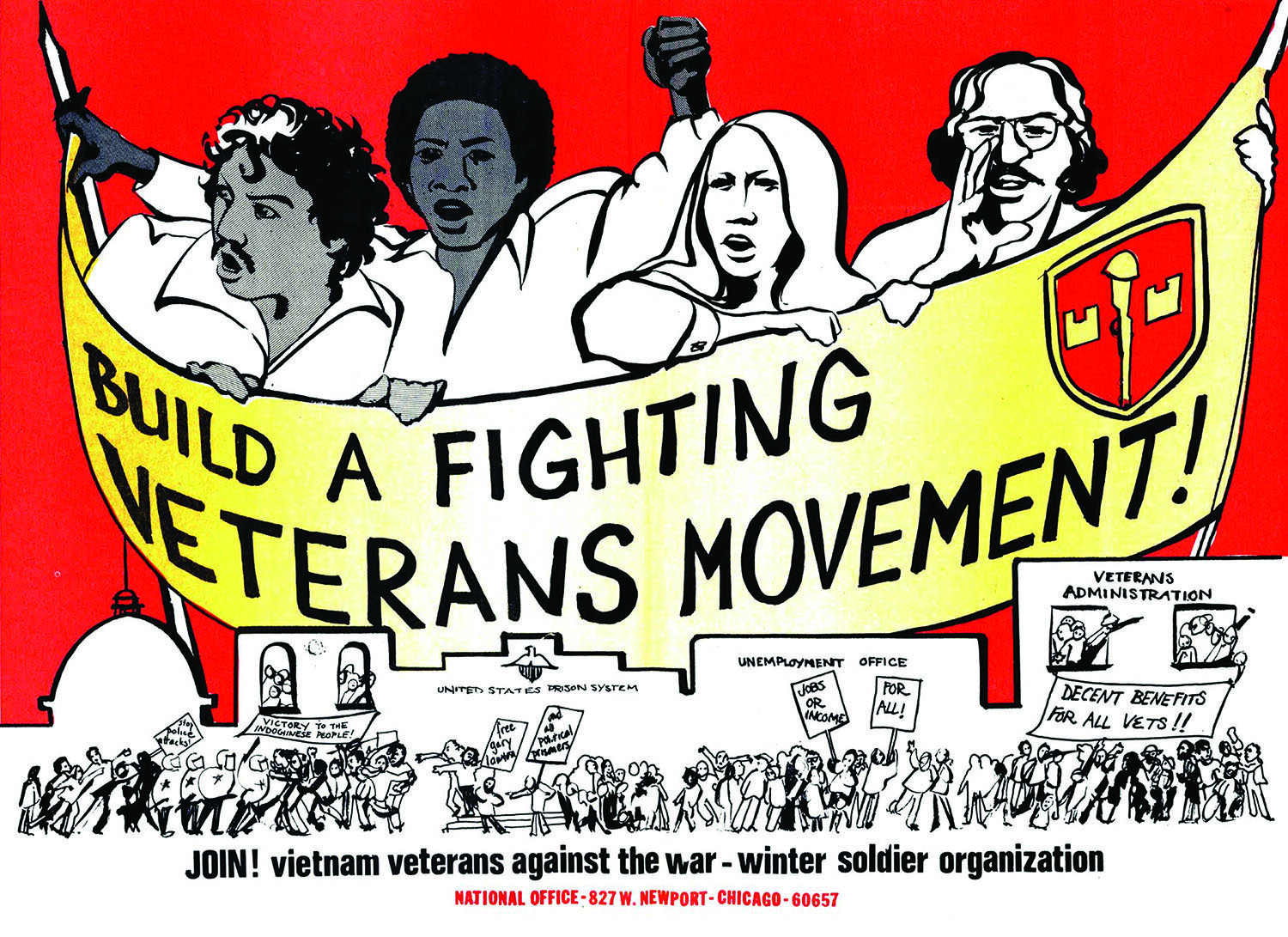

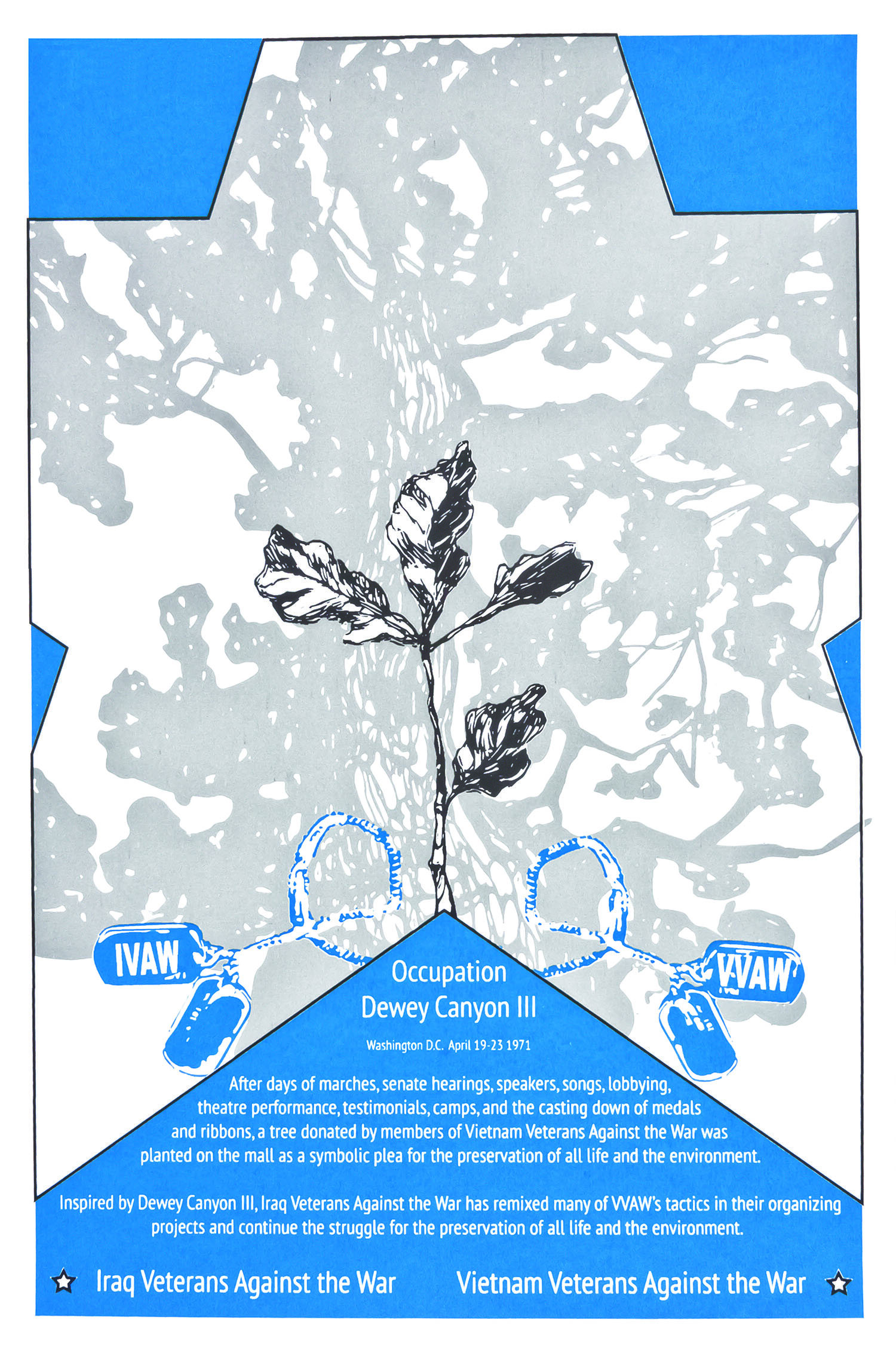

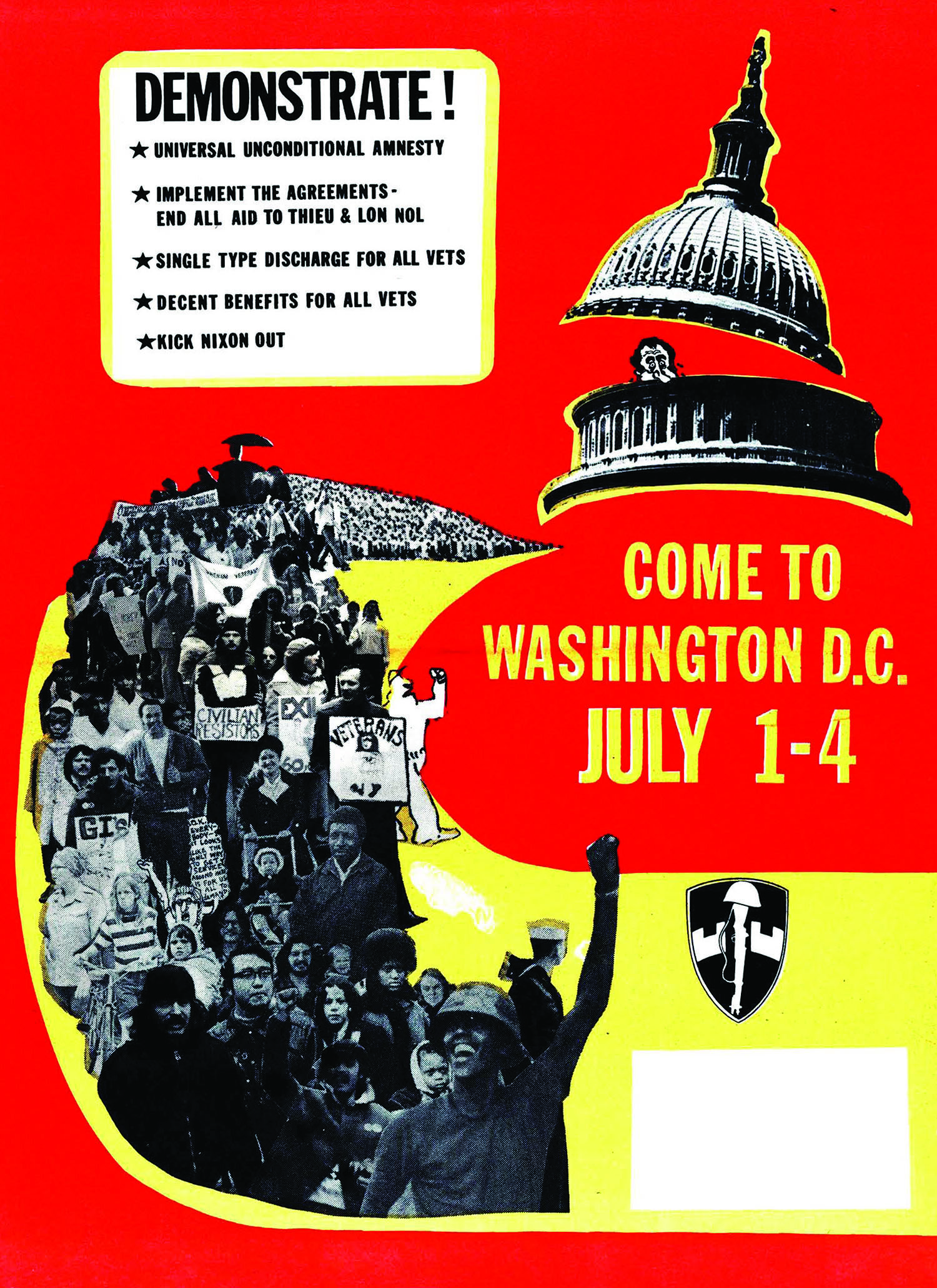

Dewey Canyon III

Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) was started in New York City in 1967 when six Vietnam veterans marched together in a peace demonstration. The organization, originally founded to oppose the Vietnam War, continues to fight for peace and justice over 50 years later.

In April of 1971, hundreds of VVAW occupied Washington D.C. for five days, in a campaign they called “Operation Dewey Canyon III” (a play on “Operation Dewey Canyon II,” a series of secret military invasions of Laos by U.S. and South Vietnamese forces). Like the Bonus Army before them, VVAW established a military encampment in the city; however, this time the veterans set up in the middle of the National Mall. Over the five-day protest, the veterans testified to Congress and led a series of demonstrations in opposition to the ongoing war.

[Dewey Canyon III protesters on the steps of the Capitol] VVAW Archive, Photos from Dewey Canyon III, 1971.

[John Kerry VVAW spokesman at microphone] Warren K. Leffler, Library of Congress Prints & Photo Archives, 1971.

[Dewey Canyon III, veteran throwing medals] VVAW Archive, Photos from Dewey Canyon III, 1971

Standing Rock

The Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, located in North and South Dakota, is among the largest Native American reservations in the United States. In 2016, despite tribal opposition, construction began there on the Dakota Access Pipeline (owned by Energy Transfer Partners), which had been rerouted to cross indigenous lands and pass under the upper Missouri River, the reservation’s primary water supply. In response, self-proclaimed “Water Protectors” — made up of Standing Rock Sioux youth, elders and others — established a protest camp in the path of the pipeline. Over the coming months, over 200 tribes from around the world pledged solidarity and joined the struggle. Then in November, after a series of standoffs with police and pipeline security forces led to injuries of Water Protectors, thousands of veterans mobilized and travelled to the reservation to support the cause. The veterans not only brought donations of supplies, but also brought military skills, however repurposing their knowledge for the nonviolent struggle.

There were so many veterans [at Standing Rock] of various eras, with a lot of military skills and training being repurposed and put to use. The work wasn’t focused on war-making, but on peace-making.

— Eli Wright, Iraq War veteran and anti-war activist

![[Medgar Evers speaking at NAACP civil rights event ca. 1960s.] Evers, Medgar Wiley, Myrlie Evers-Williams, and Manning Marable, The Autobiography of Medgar Evers. Skyhorse Publishing, 2005.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596067898900-I493W2BAHVOD34TRCAHA/2_Dignity_MedgarEvers.jpg)

![[Vietnam Veterans Against the War at Medgar Evers Grave] VVAW Archives, ca. 1971.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596071700892-M20TGGSSZZK5XXFOB5VK/VVAW-Medgar-Evers-1.jpg)

![[Leonard Matlovich reads the Time Magazine Article about himself] LeonardMatlovich.com, ca. 1975.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596067936727-PCU2LNIAB1DWIYTB756G/11_Dignity_DADT.jpg)

![[“It’s all about the climate your command creates. My command was really helpful. He told everyone, ‘She will be respected. Discrimination will not be tolerated.”] Jeff Sheng, Smithsonian, “The Faces Behind Transgender Troops’ Struggle for Acceptanc…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596068082068-TFERFF06S5PUS8OGHI4I/28_Dignity_TransExclusion.jpg)

![[Protest at the San Ysidro-Tijuana Border Port of Entry, San Diego] April Arreola, 2010.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596068169175-01ALP9QIL80D66HZSQ7O/17_Dignity.jpg)

![[Clarence Fitch was an inspiration to hundreds of young people who witnessed his strength, resilience, and clarity of vision.] William Short, VVAW, The Veteran, vol. 28 no. 1., ca. 1980s.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596068204471-9QHJ8FHG95J8QKPVAQ5P/VM-7.jpg)

![[Operation Recovery March Washington D.C., Veterans Day] IVAW Archives, 2010.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596071152454-R61GONS8KB03II2AKI64/VM-6.jpg)

![[Operation Recovery Guard Tower at Fort Hood] IVAW Archive, 2011.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596068235559-BBUNGZOED441C0K8J7CR/VM-5.jpg)

![[Afghanistan Veterans and Afghans for Peace speak at Nato Protest] Siri Margerin, 2012.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596071578985-ONE4C33AGDUFZ5MOO335/VM-13.jpg)

![[Jacob George Returns Medals to NATO Summit] Siri Margerin, 2012.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596071542269-JMCFAULMKPJTEVGUPP5K/VM-12.jpg)

![[Crop duster airplanes spray Vietnamese countryside] Creative Commons, 1966.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596068443826-0HU9JWSTFT64GJ8MJ75G/VM-9.jpg)

![[Aerial herbicide spray missions in southern Viet Nam, 1965 to 1971] The Veteran, vol. 38 no. 2, VVAW Archive.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596068391009-EGA83RH06HWIHGZZNO6G/VM-8.jpg)

![[Bonus Army aboard train cars heading to Washington D.C.] Underwood & Underwood, Library of Congress Prints & Photo Archive, ca. 1931-1932.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596069375156-HD1Y8BC4WT6MY8CC6MTR/32_Reclaiming.jpg)

![[Crowd on steps of the U.S. Capitol on the arrival of a bonus petition signed by over 1,000,000 veterans.] Library of Congress Prints & Photo Archive, ca.1922.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596069344831-5DMO0EZJ9OIS13UKRBK5/33_Reclaiming_BonusArmyMarch.jpg)

![[Veterans march to Washington to arrive at opening of Congress, December 5th, 1932 to demand cash payment of bonus.] Veteran’s Rank & File Committee, Library of Congress Prints & Photo Archive, 1932.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596071275658-16TRGGYOL0JSW7W3GGP9/31_Reclaiming_BonusArmyNewspaper.jpg)

![[Dewey Canyon III protesters on the steps of the Capitol] VVAW Archive, Photos from Dewey Canyon III, 1971.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596069991782-EIXDDT93HHRM710KLGCW/Dewey+Canyon+Three+Fred+W+McDarrah+side+by+side+3+x+11.jpg)

![[John Kerry VVAW spokesman at microphone] Warren K. Leffler, Library of Congress Prints & Photo Archives, 1971.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596069851090-W0LZDN7EVMBD0C7SD9GE/image-asset.jpeg)

![[Dewey Canyon III, veteran throwing medals] VVAW Archive, Photos from Dewey Canyon III, 1971](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58e2f18320099efd033cb97b/1596069871609-FLOE77K2OZ5QJN91EM2F/VM-11.jpg)